World Para Athletics Championships 2025: Technology static, it’s humans driving improvements in blade running

Heads turn when athletes competing in the T64 category (for athletes with one or two amputations of the legs) step onto the track at the Jawaharlal Nehru stadium at the Para World Championships. With the iconic “J” shape cloaked in dark black carbon fiber polymer, the prosthesis they wear on their legs – better known as blades – resemble high tech equipment (which indeed they are) far more than a body part and look straight out of a science fiction movie.

But while they might look like something from the future, the basic design of the blades themselves are several decades old.

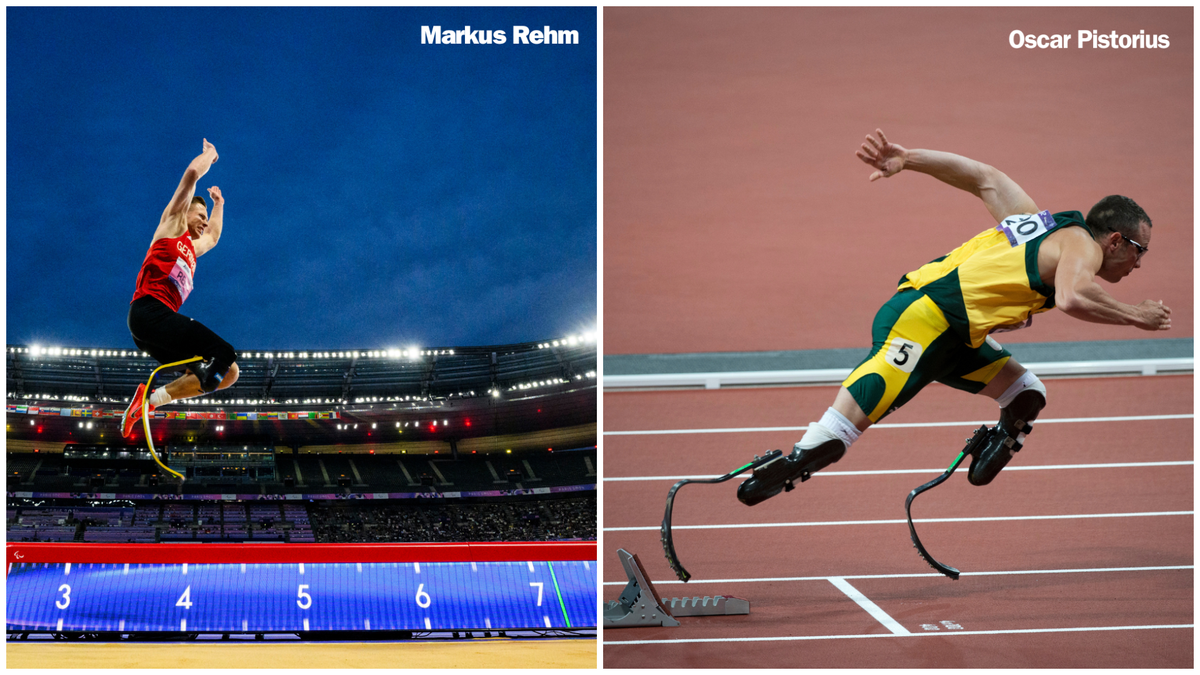

Four time Paralympic champion Markus Rehm, popularly known as ‘the blade jumper’, who will hope to improve on his world record of 8.71m in the men’s T64 category of the men’s long jump in New Delhi will be running in with an Ossur Flexfoot Cheetah blade attached to his right leg – amputated below the knee after a wakeboarding accident that he suffered when he was 14.

The ‘Cheetah’, popularised by 400m Paralympic champion Oscar Pistorius in the 2010s has been around for much longer. It’s design has been virtually unchanged since first being invented by engineer Van Phillips in 1984.

That’s not the only vintage design for blades (a catchall term since the actual prosthesis that para athletes use also includes a knee joint — over above the knee amputees — and a socket with an adaptor) that’s still around.

ALSO READ | Salum Kashafali: “What’s worse than not being able to see is being invisible”

“The current World Records in the 100m, 200m and 400m (until last year) in the T64 category are held by Johannes Floors (double below the knee amputee). He’s using blades that were first introduced in 1992. That design is older than he is!” says 100m champion at the 2012 London Paralympics Heinrich Popow, who incidently used the same blades manufactured by German prosthetic maker Ottobock.

Popow, who is now himself an equipment expert with Ottobock, says for all their futuristic appearance, the devices available for regular users are far more advanced than anything used by elite para athletes.

“For regular users, prosthetics have come a very long way. You have microprocessors, exoskeletons. Crazy stuff. When you are creating prosthetics for daily wear, it’s very different from when you are creating something for sport. For daily wear you want to have everything you can – microprocessors, batteries, sensors, AI (artificial intelligence) algorithms to predict your gait. That’s because in daily life you want all the support you can get. But that’s not what sport is about. Sport is about overcoming weakness” he says.

But options for sportspersons are limited.

There are a few simple reasons for this. For one, the iconic ‘J’ shape is mechanically near perfect — it functions as a spring by absorbing and releasing energy with each stride – critical functions for sprinting and jumping.

Secondly, World Para Athletics rules restrict just what sort of prosthetics are actually allowed.

Every athlete in the T64 category, for instance, is assigned a MASH (Maximum Allowable Standing Height) during classification for their event. That’s the maximum height an athlete might be when standing while wearing their prosthetic blades. If they exceed it, they can’t compete.

“You also can’t just debut a new design,” says Popow. “The WPA says any blades being used have to be in use for at least nine months,” he says.

Indeed it’s not that manufacturers can’t make radically different designs – they just aren’t allowed to.

“If it was allowed you could absolutely create something far superior to what athletes are using now. But then you might need to put a motor or increase the length of the blade which would be the easiest way to make a faster runner and then that won’t be fair anymore. That would almost be like doping,” says Andrea Cremer, technical manager at Ottobock.

So for now, it’s only tweaks that can be made to blades – think more layers of carbon fiber to make blades stiffer for heavier athletes — rather than radical shifts in shape or technology.

But according to Popow, what’s already available is more than sufficient.

ALSO READ | Blade, wheels, and grit: How Indian para athletes are getting access to specialised equipment

The blades that para athletes use are already made out of carbon fiber. That’s already stronger than the human body. Right now the technology may be from the 1990s but even that is far ahead of what humans can achieve themselves,” he says..

Far ahead, says Popow but not as far ahead as it once was.

“The technology has not changed that much since my time as an athlete. But what’s changed massively is the level of athleticism and professionalism of para athletes. Since London 2012, the athletes have become more professional. The level of education not just of athletes but also of coaches and technicians has gone up dramatically,” he says.

So much so, that in many cases there have been arguments made that para athletes using prosthesis have started not only to become competitive with their regularly abled counterparts but also superior to them.

Take for instance Rehm, who apart from his four Paralympic titles in long jump also finished first at the 2014 and 2015 German National Championships. In Rehm’s case though, his able bodied compatriots complained that he had an unfair advantage and eventually forced his removal from the team that would compete at the 2015 World Championships. And so Rehm continues to compete amongst Para Athletes – although his personal best jump of 8.71m, would have been enough to win gold at every world championships but the 1991 edition when Mike Powell set the still standing able bodied world record of 8.95m.

While Popow understands the urge for para athletes to compare and compete against able bodied ones, he disagrees with the idea that the two should be compared.

Heinrich Popow

| Photo Credit:

JONATHAN SELVARAJ

Heinrich Popow

| Photo Credit:

JONATHAN SELVARAJ

“I don’t like the argument that’s made that these devices give an unfair advantage. How is it an advantage to lose your leg? Markus’ disadvantages are far more than any advantage he might have from wearing blades. But at the same time, it doesn’t make sense for para athletes to compete alongside athletes without disabilities. The mechanisms for force generation is completely different. Regular athletes speed is based on kinetic energy but in the Paralympics, speed is a matter of compression of the blade, energy loading into the blade and then returning. If you try to bend your foot the same way as you do a blade, it’s only going to break so the two events are just not comparable. You can’t look at para sport from the same eyes as regular sport,” he says.

Popow says the reason why para athletes want to compete with regular athletes is mostly to appeal to fans of the latter but this is short sighted.

ALSO READ | A turning point: How domestic classification is transforming para sports in India

“It’s understandable to want to have the same kind of viewership at the Olympics have but Para athletics is its own unique sport. The solution to get the kind of attention we deserve is to build up the sport,” he says.

That, he says, can be done without any changes to equipment. “I started as an athlete with the same kind of blades as the ones athletes are using today. At that time, the question was whether someone would break 5.50m in the long jump. That was done. After that, people started crossing 6m. Then 6.50m. Now everyone is jumping over 7.5m. And Markus is jumping 8.71m,” he says.

Popow only expects that mark to get bigger.

“If there will be a jumper that jumps over nine meters at the Paralympics, I promise you everyone will watch the Paralympics. I don’t think we are very far from a nine meter jump. I’m confident that we will see it before Los Angeles.”

All this, he says, will come using the same technology that exists today and that has existed for the past couple of decades. “It’s like if you sit in the same car as Max Verstappen, you still aren’t going to become a Formula 1 champion. It’s not the technology that drives the human, it’s the human that drives technology,” he says.

Published on Sep 29, 2025