Krishna Jayasankar goes beyond basketball lineage, set to become first Indian woman to compete in NCAA finals

It’s rare for a 23-year-old to have stayed off social media for as long as she has, but a few weeks ago, Krishna Jayasankar Menon finally opened an Instagram account in her name. And, she’s already receiving plenty of messages — for good reason.

On June 14, with her opening throw in the women’s discus at the NCAA (National Collegiate Athletic Association) Championships, the 23-year-old will etch her name into Indian sporting history. Representing the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV), she will become the first Indian woman to compete in the final of the NCAA Track and Field Championships — the premier collegiate athletics competition in the United States and widely regarded as the highest level of college sport worldwide.

Another Indian, Sharvari Parulekar, will also match Krishna’s milestone by becoming the second Indian woman to compete in the NCAA finals. She will take part in the women’s triple jump in Oregon, just about half an hour after Krishna’s event.

While the number of Indian athletes competing in the NCAA has been growing in recent years, there are still only a handful who have competed at the highest level. Krishna is just the fifth Indian track and field athlete ever to make the NCAA finals, following the likes of Mohinder Gill, Vikas Gowda, Tejaswin Shankar and Lokesh Sathyanathan.

As the clock ticks down to her event, Krishn is raring to go. “I’ve heard so much about Hayward Field. This is where the World Championships were held (in 2022). I want to show up and show how much work I’ve put in. I’m really looking forward to representing our country, India, my family and the entire UNLV University,” says Krishna, who qualified for the NCAA finals by finishing in the top 12 at the West First Rounds in Cushing, Texas on May 31 with her career-best throw of 55.61m.

But while she’s coming off her personal best, competition at Hayward Field will be tough. Krishna is currently the overall 12th-ranked thrower in the USA collegiate circuit. The field at the NCAA finals includes Paris Olympics qualifier Jayden Ullrich (SB 64.81m) and Caisa Marie Lindfors (59.03m), while Cierra Jackson is one of the event’s favourites with a season’s best of 64.38m.

For now, Krishna is counting the blessings she already has. “It’s going to be a win just because I’m competing in Eugene itself. This is a win not just for me but also for the 12-year-old girl who dreamt of going to the United States, who dreamt of living this life, and is actually living this life. I want to make that 12-year-old in me proud — that she made all the sacrifices she had to, overcame all the adversities and obstacles she faced, and broke all the barriers she did to become the woman she is today,” says Krishna.

Krishna Jayasankar with her family.

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Krishna Jayasankar with her family.

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Growing up in Chennai, it was probably inevitable that Krishna, the daughter of Jayasankar Menon and his wife Prasanna — both of whom captained the Indian basketball team — would have potential as a sportsperson. While her father is 6’5”, her mother is 5’9”. Krishna has got the best of both sides of that gene pool. Standing a statuesque 5’10”, she is a powerfully-built athlete, with a 225kg quarter squat and a 100kg clean and jerk among her numbers in the weight room.

Body image issues

However, the physique that has made her one of India’s top throwers had her dealing with bullying and body image issues during her childhood. “I think there are a very few people who actually have the same body type as me. And because I didn’t fit the perception of how an Indian woman looks, I was made fun of. I was fat-shamed by my classmates. I actually loved dancing — I was even part of the school dance team — but there were so many opportunities I was deprived of because I didn’t fit the perfect realm of how an Indian woman looked,” she says.

During her schooling in Chennai, Krishna was nudged into the throws event for the same reason. “I actually started throwing the shot put when I was in fifth grade because my PT teacher thought I was the right size and shape for it. She was just trying to look out for some people who were very tall and stocky. And I fell into that category because I was taller than my entire fifth grade group. That’s the perception people have — if you are tall and a little plump, you’ll probably be good as a thrower,” she says.

Although she hadn’t organically chosen the event, Krishna would learn to love it. “I actually started with the shot put and I became fascinated by the way it left my hand and how I was able to make it fly with so much power. I liked how strong it made me feel. That’s how I fell in love with track and field,” she says.

It wasn’t a wrong choice. Krishna would go on to compete and win medals in the shot put at the CBSE state level and break the CBSE national record. Eventually, with the intention of developing as an athlete, Krishna enrolled in the Tenvic Academy — the sports academy founded by former Indian cricketer Anil Kumble — in Guntur.

It was there that Krishna would first meet Jamaican throws coach Michael Vassell. “Until then I’d only ever thrown the shot. But he was the first one who suggested that I had a wide enough wingspan and could throw the discus too. That’s when I really started competing in the discus,” she says.

Kirishna Jayashankar: I definitely want to compete at the 2028 Olympics. I’m going to start my Masters in Sports Management at UNLV, but I will be taking the time to come to India to compete next year so I can make the Indian team for the 2026 Commonwealth and Asian Games.

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Kirishna Jayashankar: I definitely want to compete at the 2028 Olympics. I’m going to start my Masters in Sports Management at UNLV, but I will be taking the time to come to India to compete next year so I can make the Indian team for the 2026 Commonwealth and Asian Games.

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

That wasn’t the only thing Vassell suggested to Krishna. “He was the first coach who suggested that I could consider applying for a sports scholarship to compete in the NCAA. That was the first time I learned that it was even a possibility — that I could study in the USA. That was when the dream first came to me,” says Krishna.

That dream persisted even after Tenvic shut down during the pandemic, and Krishna returned to Chennai. “At that time I was really desperate to compete in the NCAA, but I wasn’t sure how that would happen. And then coach Vassell suggested I come and compete for some time in Jamaica,” she says.

Krishna’s parents had taken their time to agree to her training in Guntur. Jamaica was all the way across the world. But Krishna was adamant. It was a decision that changed her life.

ALSO READ | Indian track stars chase the American dream at the NCAA

“Going to Jamaica gave me the kind of exposure I needed to make the move to the NCAA. Many US coaches, because of the proximity and the reputation of Jamaican track and field, are interested in working with Jamaican athletes. A lot of coaches come there personally to recruit athletes,” she says.

Jamaican journey

It wasn’t that there were no challenges. “Jamaica took some getting used to. I was an 18-year-old Indian girl. Jamaica is a beautiful country that I consider my second home, but there is the safety aspect I couldn’t ignore. I was staying with coach Vassell at his home, and I’d travel an hour by public bus every day to go to school and train. As a kid in India, I was always pampered, and my parents were always there to help me if I had any challenges. But in Jamaica, I was almost on my own. I learned what independent life meant. I was a girl when I went to Jamaica but became a woman when I left, because I matured so much,” she says.

Krishna competed in a number of national-level competitions in Jamaica and even managed to throw a then personal best of 48.27m at the Olympic Destiny Series 3 in Kingston. It was one of a number of performances in Jamaica that eventually saw Krishna scouted and earn a scholarship to the University of Texas in El Paso.

But just because she had accomplished her dream of studying and competing in the NCAA didn’t mean everything that followed would be smooth sailing. After her first year, she transferred to the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. Just as she made the move, the then throws coach Dorian Scott — who had recruited her in the first place — was relieved of his duties.

For the next year, Krishna was without a coach. Matters worsened after she picked up multiple injuries that prevented her from competing at all.

“2023 was very tough for me. There was a span of several months where I had no clarity as to who’s going to coach me, what’s going to work. Then I ended up fracturing my hand while doing a box jump. Before that, I’d also torn my shoulder when I was leaving the University of Texas at El Paso. It was very strange,” she says.

That season, says Krishna, was one of the lowest periods of her athletic career. She worked on improving her mental health and, with sport not in the picture, attempted to focus on her studies — even making the dean’s list that year.

While she eventually recovered from her injury and also started working with a new coach, things were slow to improve. Following a poor season, she lost part of her scholarship in 2024 and has had to take up a part-time job. Currently, Krishna works at a sports stadium to cover some of her expenses while still maintaining her grade average and training routine.

There are days when Krishna admits she questions what she’s doing at all. “It’s not easy. Some days I’ll call my dad or my mother, my sister or my psychologist and I’ll be crying. I didn’t think I signed up for this. I had a really nice life in Chennai. I was safe, and my mother and father were always there to take care of me. But I always remind myself that I had to take this path. I wanted to be different. I’ve always felt that life really starts when you step outside your comfort zone,” she says.

Turnaround season

Things have begun to turn around for Krishna in 2025. She’s recorded personal bests in both the shot put and the discus — the latter breaking a 26-year-old school record with a throw of 55.22m. “What helped my technique in both events was that I actually got very strong in the gym. I’m maximising the speed at which I’m making my lifts. That has really helped me. There are also a few technical corrections that Coach Jordan and I have worked on. I’m trying to be as patient as I can when I enter the ring and rotate. I’m also focusing on how I land in the middle. I am trying to land at a particular angle. There were times I would extend myself to the left sector of the ring and foul most of my throws,” she says.

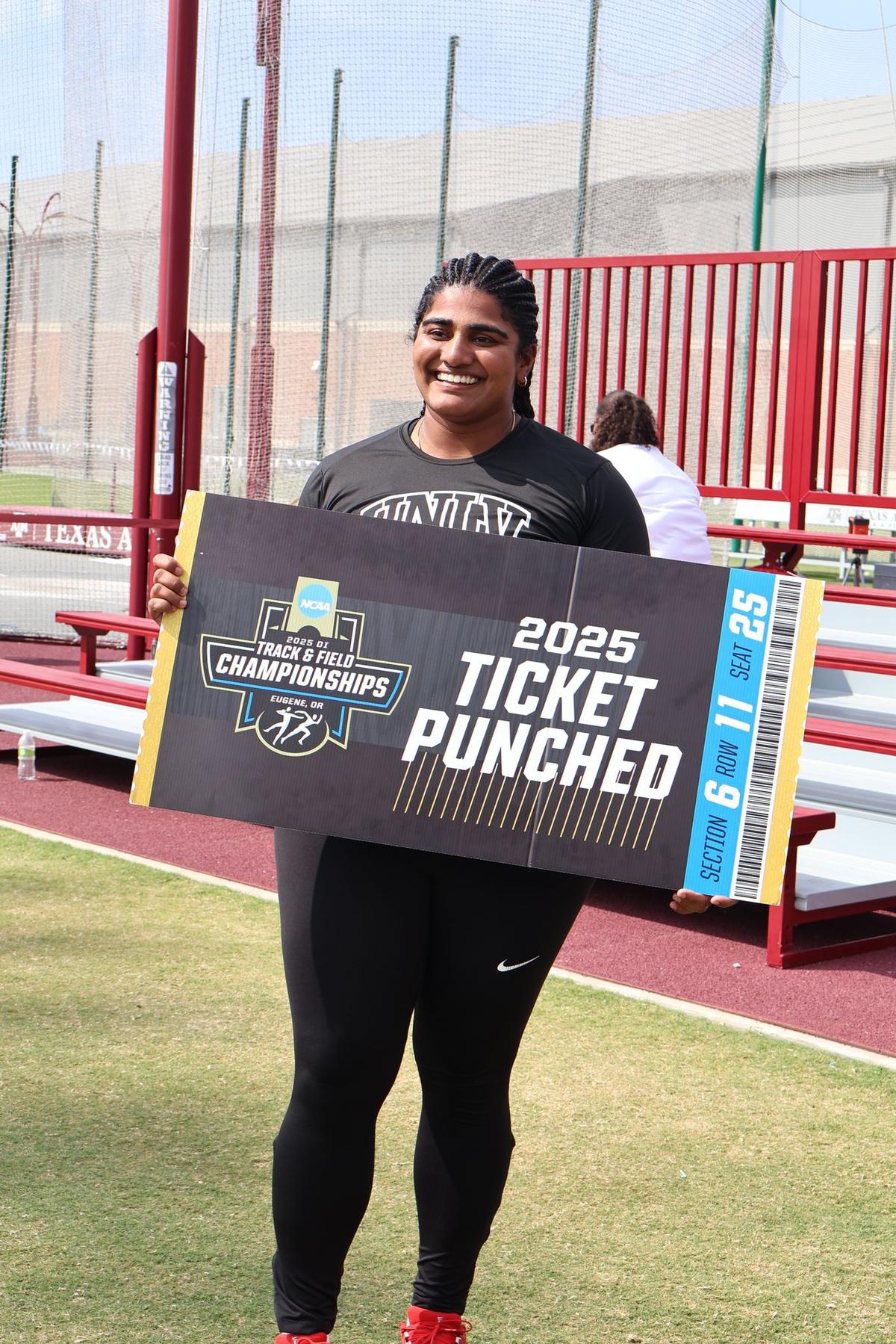

Krishna Jayasankar after securing her spot in the NCAA finals.

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Krishna Jayasankar after securing her spot in the NCAA finals.

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

That improvement in strength and technique has brought about an improvement in form that’s come at exactly the right time. As an NCAA athlete, she was eligible for five years of competition, meaning the NCAA national finals will be the last outdoor competition of her collegiate career. As such, she’s hoping to make this final opportunity count. “I know that I’m way more capable of breaking the school record. I also know that because this is my last discus send-off, I want to end it in style. I want to make another PB if possible in Eugene,” she says.

There are longer-term goals too. “I definitely want to compete at the 2028 Olympics. I’m going to start my Masters in Sports Management at UNLV, but I will be taking the time to come to India to compete next year so I can make the Indian team for the 2026 Commonwealth and Asian Games. But what I really want to do is compete at the 2028 Olympics,” she says.

And while she’s hopeful of performing well in Eugene, Krishna says she’s grateful for all that she’s achieved. While the big throws and medals are great, perhaps what she’s most grateful for is the way she now perceives herself. “When I compare myself to who I was when I was 12 or 13 years old, I can’t recognise myself. That young girl would constantly seek validation from people. I’d always think, ‘Oh my God, should I buy this? Would this look good on me?’ Those were constant mental challenges. But ever since I’ve started college, I’ve met people who really envied the way I looked. They saw my achievements and saw my inner beauty as a person. That stood out more than just how my body looked,” she says.

There are those from her past who notice her living her best life as well. “A lot of the same people who made fun of me and spoke badly about me are now commenting on my Instagram saying how I ‘made it’. They’ve reached out and are saying great things about me. It shouldn’t matter, but I smile when I see those messages. When your haters have to talk good about you — that’s a W right there,” she says.