Javier Sotomayor Interview: The Mind, Method and Mystery Behind High Jump’s 2.45m World Record

In a career that spanned three decades, Javier Sotomayor earned a place among the greatest high jumpers of all time, winning an Olympic gold, four World Championship titles, and setting the world record of 2.45m.

Speaking to Sportstar on the sidelines of the Ekamra Sports Literature Festival, the now 58-year-old reflected on taking up the high jump despite being afraid of heights, his never-ending chase for perfection, why his record still stands 32 years on, and why he is not sure he could break it if he were competing in the modern era.

You set your record in 1993. Thirty-two years later, it still stands. Why do you think that is?

I know how I broke the world record in 1993, but I can’t explain why it has lasted so long. Competition played a role. I was fortunate to compete in what I believe was the best era of high jump. We were not making fluke jumps. It wasn’t about performing well on just one day or in one season. We were jumping consistently at a high level over multiple seasons.

The world record is 2.45m, and I didn’t reach it suddenly. It was an evolution, and that comes from competing regularly against strong athletes. I was lucky to get the chance to compete against champion athletes from the time I was 16.

That is what pushed me constantly, and it helped me achieve the maximum that I could.

You also had a very unique technique.

Compared to most other jumpers, I had a very long final take-off step. For most people, the last step just before the jump is short, but mine was long because I was trying to combine two techniques, almost two types of jumpers, within myself. One who depended on speed, and the other who depended on the force generated at take-off.

I did that because I wanted to produce as much force as possible at the moment of jumping, which meant I had to generate maximum speed. That demanded a great deal of preparation, training, and stretching. Along with that came physical therapy and constant jumping practice to ensure that my ankle stayed healthy. Even when I was off the track, I had to keep working on my ankle. Otherwise, I would have broken down quickly.

So I put a lot of effort into strengthening my ankles because there was always going to be heavy impact and a great deal of stress on that joint.

My technique was something I taught myself because it went against what the coaches expected. I stuck with it even when they wanted to change it. Theoretically, this was not the ideal way to jump, and initially, my trainer did not believe in it. But in the end, I convinced him that this was the way I wanted to jump.

Why do you think people haven’t tried to duplicate your technique?

I think some people have tried to, but each athlete has to find the technique that works for him. Some depend on speed, while others generate a lot of force at the take-off point. My son also does the high jump. He is 17, but he is not competing at the highest level right now. I don’t advise him to copy me either, but he still tries to.

You say your technique is very self-made. How much of your success is purely talent and how much is due to hard work?

I would say it was a balance of both. Some athletes worked just as hard as I did but were not able to jump as high. And I have also known athletes with enormous talent who did not work as hard, and as a result, did not achieve the same results.

Did you always want to be a high jumper?

When I was very young, I was actually afraid of jumping. I was afraid of heights. I started around 10 or 11, and at first, I did not want to do the high jump simply because of that fear.

I was a kid like everyone else. I played a lot and went to school. Around the age of 10, I became serious about sports. In Cuba, there is a lot of emphasis on physical education, and that helps. Many of us love baseball more than other sports, but from a young age, I wanted to be an athlete. The sports I really enjoyed were running and the hurdles. I also liked the triple jump a lot.

In Cuba, athletics education means you have to try different disciplines. It turned out that I was good at the high jump, and when I was around 14 or 15, I decided to specialise in it.

How hard is it to be an athlete in Cuba, given the number of sanctions on your country?

In the 1980s, when I started, there were sanctions on Cuba, just as there are even now. Back then, though, despite the challenges, they did not completely close the door on us. I was able to compete in the United States many times. Today, it is much more complicated for Cuban athletes because visas are often denied. In my time, I did not face that kind of refusal.

In those days, there was also much stronger government support because we had greater resources. Countries like Russia and East Germany used to extend significant support, including financial help. Now our economic conditions are such that sport cannot receive the same level of backing as it once did.

The international situation is also difficult for us. Our athletes across age groups get far less international exposure than before. Earlier, even youth athletes were able to travel and compete abroad. The positive change today is that athletes receive a larger share of the prize money they earn overseas or through sponsorships. The personal financial return is higher.

Despite all the challenges, Cuba has consistently performed better than most countries in world athletics for a nation of its size. Why do you think that is?

I think the results of Cuban sports infrastructure are there for everyone to see. There was talent scouting among young children, and there were follow-ups after that.

First, you identified talent, and then you continued to nurture it. There were dedicated sports schools for teenagers where they could be closely monitored and supported. At that time, the sports infrastructure, facilities, training, support systems, and competition were all much better than they are today. We used to have coaching supervision almost every day of a child’s life.

The coaches were at a very high level. Every coach who trained a high-performance athlete had to undergo formal training; without that, they were not allowed to coach. There was a great deal of accountability. There were people above the coaches who ensured that they were actually training and continually studying their profession. This multi-level supervisory system made a big difference.

Even though Cuba was a very strong sporting nation, you were one of its biggest stars. How much pressure was it being one of the country’s top athletes in the 1990s?

It was challenging because we were already used to seeing people win. At the 1992 Olympics alone, we had 31 medallists. So, it was never enough just to medal. If I went to a World Championships, the expectation was to win. If I did not, people would look at me strangely. The expectation was always to win gold. If I ended up with silver, it was seen as a disappointment.

National icon: Cuban President Fidel Castro honours Javier Sotomayor, the nation’s most soaring symbol of excellence, whose world record of 2.45m was forged in an era when Cuban athletes were expected not just to medal, but to win.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Photo Library

National icon: Cuban President Fidel Castro honours Javier Sotomayor, the nation’s most soaring symbol of excellence, whose world record of 2.45m was forged in an era when Cuban athletes were expected not just to medal, but to win.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Photo Library

You won several World and Olympic medals, but also missed out on some major competitions. You might have won another Olympic medal if not for Cuba’s boycott of the 1988 Games. Does that still bother you?

Not just the 1988 Olympics, I could also have competed at the 1984 Olympics as well [Cuba boycotted both the 1988 and 1984 Games]. But especially in 1988, I was in the best form of my life. It hurt that I could not compete. If I had gone in 1988, I would have definitely won a medal. That is why the 1992 Games were so important. The Olympics are the biggest tournament in anyone’s career, and for me, it was a personal challenge. I had to take advantage of the opportunity I had lost.

It wasn’t even that I had lost an opportunity. It was that I did not even go. The challenge I set for myself was that now that I had the opportunity, I had to seize it. I think it was one of the most important competitions of my career.

You won gold at the 1992 Olympics but faced disappointment in 1996. Could you reflect on that experience and how you came back from it?

I took part in three Olympic Games. In 1992, I won gold. In 1996, I had a knee injury, and then in 2000 I won a silver. I might have done better in 2000, but it was raining during that competition, and I never performed well in the rain. So even though I have two Olympic medals, the Olympics were actually not my best sporting moments. In 1996, my coaches did not want me to compete because my knee injury was very bad. I jumped 2.29m, but it was not one of my better competitions.

That year, I promised myself, my family, and my coaches that I would quit the sport if I did not win a gold medal at the next year’s World Championships. I was clear that even if I won a silver or a bronze, I was going to quit. I had to win a gold.

Did you visualise yourself winning that gold medal at the 1997 World Championships?

I really started learning the art of visualisation in 1996, when I spent six months without making a single jump because of my injury. I had been doing visualisation earlier as well, but those six months were when I did it every day.

My psychologist and I mapped out the entire process precisely: the time to concentrate, the run-up, the impulse step, the final motion, the jump, the flight time. We traced all of that out with my fingers. When I jumped 2.45m, I had already visualised it in my mind. In my visualisation, I could see myself improving, going from 2.30m to 2.35m and then to 2.45m.

Would you visualise your technique during a competition, say at the top of your run-up?

At the start of my run-up, I always focused on my technique. I’d think, “What is the speed I’m going to run at?” I would think, “What’s the power I’m going to generate?” I was always visualising the jump.

These days, the high jump is extremely data-driven, with a strong focus on biomechanics. In your time, how did you prepare for such a technical event?

In my time, the only thing we had were sequential photographs of the different stages of the jump. Sometimes there were live screenings of jumps from other competitions, but in Cuba, there was not even that. We had to depend only on the photos. At a later stage, we did get some technical tools, but nothing like what is available today. They were very rudimentary.

It was difficult even to communicate with my family when I was away for a competition. I had to look for a telephone, and I could not even use the ones in the hotel because the charges were too expensive!

What do you think you might have achieved if you were competing today with all the available technology, specialised support, and modern equipment?

This is a hypothetical question. It is true that technology has advanced a lot now. The weight of just one of the shoes I jumped in would probably be more than that of a pair of jumping shoes that athletes use these days. There is also far more technical knowledge now in terms of medical support and muscle training. We had injuries that put us out for six months. These days, you can recover from those in maybe one month.

Back then, it wasn’t easy to get knowledge. Today, you can just put somebody’s name on YouTube, and the whole analysis of your competitors will come up. I remember that in the 1990s, I had to hand-crank a film player just to watch one minute of video footage. There was no slo-mo, no special cameras like today.

Today, my son is training in Spain, and I can help him from Cuba. I can look at his video and tell him where he has to do better.

But at the same time, I don’t think you can compare the two eras.

If I had all those facilities, then maybe I wouldn’t have been as mentally prepared, keyed in, and focused as I was back in the day. Additionally, I think what helped me was the kind of competition I had. It wasn’t just the jumpers I was competing with, but also my teammates who were training with me in Cuba. They were very serious athletes, and we trained really hard with each other.

What, according to you, is a perfect jump?

It starts when I concentrate well. I start running at a good speed and, more importantly, develop a good rhythm. After that comes a powerful take-off and then the jump itself. Each position should come at the right moment. And finally, you need to enjoy your jump. When all of this comes together, you really get joy out of it. You feel as if you are flying!

Did you ever make a perfect jump?

I don’t think I ever did a perfect jump, although I always dreamed about it. I was always chasing that jump. I think there were jumps where I did not clear 2.45m, but those were executed almost perfectly, according to what I was visualising.

That is why I think that, mentally, the high jump is the most difficult discipline. Your best effort might not be what you are truly capable of. For example, if you execute your most technically perfect jump but the bar is set at 2.30m, then only 2.30m will be recorded against your name, even if you feel you jumped well beyond that. And then, when you have to attempt 2.37m, you might not produce your best jump. Sometimes your medal-winning jump might not even be your best jump. That is very different from something like the javelin, where your technically best throw is usually also your longest.

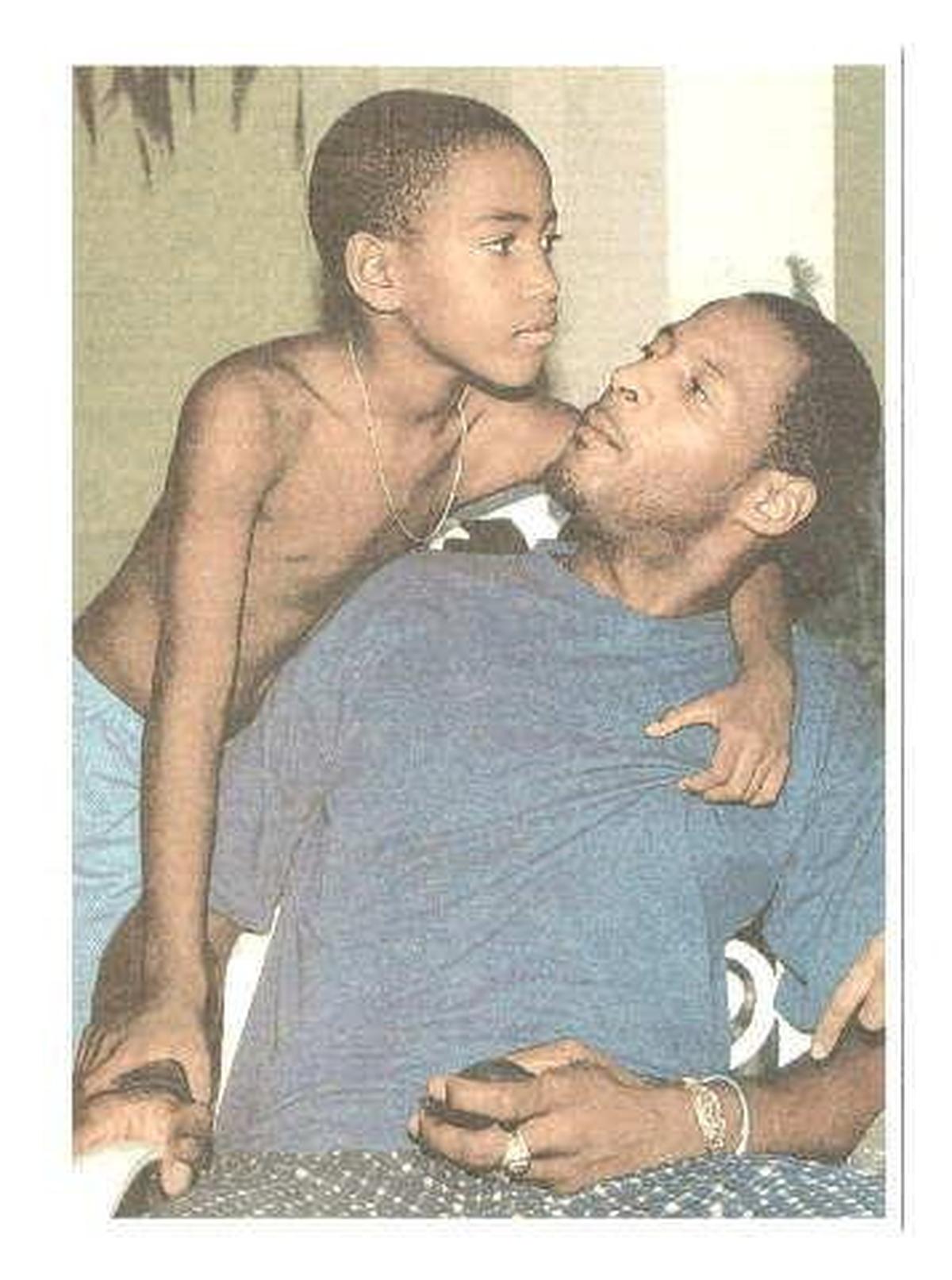

Fear factor: “When I was very young, I was actually afraid of jumping. I was afraid of heights. I started around 10 or 11, and at first, I did not want to do the high jump simply because of that fear, says World-record holder Javier Sotomayor, seen here with his son.

| Photo Credit:

AP

Fear factor: “When I was very young, I was actually afraid of jumping. I was afraid of heights. I started around 10 or 11, and at first, I did not want to do the high jump simply because of that fear, says World-record holder Javier Sotomayor, seen here with his son.

| Photo Credit:

AP

Do you think you achieved what you wanted to?

Since I was 15, my goal has been to be the best in the world. At that age, my immediate target was to be the best in the youth category.

Once I achieved that, I thought, “Now I want to be the best in the world.”

By then, someone had already jumped 2.42m, so I knew I had to do better than that.

But even after I became the best in the world, I always wanted to do better than myself. I kept setting the bar higher.

Even though I was never able to go beyond 2.45m, in my mind, that was always possible; that was always the target. I wanted to reach 2.46 or 2.47m. So by my own assessment, I fell short a little bit.

That is why I repeat that the most important thing is what is in the mind of the athlete, the desire to be better than yourself every single day.

Published on Dec 08, 2025