Indian hockey team now has a deeper understanding of what the mental side of game means, reckons Paddy Upton

Following a disappointing performance at the 2023 World Cup on home soil, the Indian men’s hockey team made a remarkable comeback, winning gold at the Asian Games and a second consecutive Olympic bronze at the Paris. This turnaround was significantly aided by mental conditioning coach Paddy Upton, known for his Midas touch in sport.

However, Craig Fulton’s team recently faced another slump with seven consecutive losses in the European leg of the FIH Pro League 2024-25. Now, with a spot in next year’s World Cup on the line at the Asia Cup 2025 in Rajgir, the team is once again looking to the South African to help it navigate high-stakes pressure and regain its winning mentality to end a five-decade-long medal drought — India’s last podium finish at the World Cup was in 1975.

In an interaction with Sportstar, Upton, a master of the mind known for his success in sports, shares insights on his role, the strategies he’s working to help the Indian team navigate the pressure, manage distractions, normalise failures and unlock its full potential as it aims for the ultimate prize.

Excerpts:

Q. When a team goes through a string of bad performances or bad results, how do you motivate them? What kind of conversation do you have with the players?

A. Just talk about the process. If we’re following a great process and we’re losing, there’s no problem. But if you’re losing because we’ve gone away from some of our disciplines, then we focus on bringing our disciplines back.

If we have strong processes and great disciplines in place, a talented team will see the results go their way over time. It’s about what we can control: our process. The results are a natural outcome of getting that right.

Q. What kind of mindset are you planning to cultivate for the players, given their incredibly demanding schedule next year with the HIL, Pro League, Asian Games, and World Cup?

A. Being a champion requires a two-pronged approach: individual professionalism and a strong team mindset. On an individual level, every player must be fully professional in every aspect of their preparation. From a team perspective, we have meticulously analysed the behaviours and attitudes that define excellent teams versus those that underperform. This has given us a clear roadmap for success, which we did with the Olympics.

We know that teams that win major tournaments don’t just become champions in the final game; they arrive as champions. They eat, sleep, train, and recover like champions, treating every aspect of their preparation with the utmost professionalism. The victory in the final is merely a confirmation that they have been on the right path all along. It’s about setting up all the necessary champion processes and being the best in the world at all the small elements of the sport, well before the final game.

Q. What was the Indian hockey team’s mental state like when you first met them, and how has their mindset evolved to where it is today?

A: I think there’s a greater awareness in each individual of how their mind works and how to manage it, both individually and as a team. There is now a deeper understanding of what the mental side of the game actually means. For example, one of the key pieces of mental coaching is distraction management.

Players on our team, both as individuals and as a group, are developing a greater understanding of the types of things that distract an individual or a team. We’re learning how to prepare for and recognise these distractions when they happen. Some practical examples of distractions include scoring or conceding a goal, seeing the scoreboard when you’re two goals down with a quarter to play, huge crowds, a final, a card, or a refereeing decision. Players can often get caught up worrying about these things for a while—for instance, worrying about a referee’s decision for a minute after it happened. In that time, you can make a mistake that costs your team.

So, it’s about recognising, both individually and as a team, what distractions are and how to quickly recognise them and help each other get back on track and focused on the game. A lot of it is about awareness and finding a way back to focus on your job as quickly as possible. For 90% of the game, everything is fine; it’s when things go wrong that you lose. That’s where we really come to understand and recognise those moments and course-correct as quickly as possible, hopefully before the opposition can, so we can capitalise on that.

Q. Even at the elite level, is there still stigma among athletes to open up about their mental health?

Yes, I wouldn’t say there’s a stigma there. The thing with athletes is they’re so used to covering up their doubts, their negative thoughts, and their vulnerabilities and insecurities. This is because if a coach sees it, the coach will drop them; if an opponent sees it, the opponent will exploit it. But the reality is that all 22 players on the field are 100% guaranteed to have doubts, vulnerabilities, insecurities, and negative thoughts.

They’re very good at hiding these things in a professional context, which they need to do for professional preservation. But then, when they get out of that context, they need to understand that to move through something and not have it get stuck and create noise—whether mental or physical—they need to find a safe enough place to be able to speak about it. They also need to be secure enough within themselves to know that speaking about a vulnerability and insecurity, particularly as an athlete, is a strength, not a weakness.

For too long, it’s been labelled a weakness, and even more so in male sports than female sports. But hopefully, that’s changing. My message to players is always this: if something is bothering you and you’re thinking about it more than is necessary, you don’t have to talk to everyone, just talk to somebody. This allows it to come out and free you up to carry on. Do all players do that? No. Are we still going to have problems with players holding in and trying to hide things? Yes. Is that going to disrupt their performance and their lives? Yes, but hopefully less and less.

Q. What are some of the common mental blocks that athletes come to you with?

A. It’s actually very simple: pressure. Pressure is always about how crucial the amount of importance we place on a result in future. So that’s why finals have maximum pressure, because pressure always comes from the importance of a result, and it’s always about the future. We can’t deal with the future. So pressure builds in our body. So that’s number one.

Facing success causes pressure, running away from failure causes fear of failure. There’s worrying about being dropped, worrying about making mistakes, worrying about being eliminated; goalkeepers worrying about conceding a goal and what other people say. So, fear of failure is the second one.

The third one would be off-field distractions. It’s really big in my experience. It’s probably about 1/3 of all distractions that athletes face. Parents being sick or a loved one being sick, an argument within the family, financial problems, maybe a legal issue or some indiscretion that’s come up in their private life that is threatening to become public, which we’ve seen happen with some athletes. So off-field issues, and that’s something that very few players will talk to a coach about. Partly because this environment is professional and it’s about hockey, but coaches and players need to realise that as many as 1/3 of all distractions actually don’t have anything to do with the sport.

And probably the fourth biggest distraction is when you have an unhealthy team environment, when there’s politics within a team, or a player doesn’t feel like they’re being respected, or the communication is not good, or someone’s given a role that they don’t really agree with, but they don’t have a voice to talk to the coach. And that’s where coaches, captains and senior players come in.

The real responsibility for creating a great culture where players feel most engaged, most comfortable, and most free to speak, and that’s not a sporting challenge. That’s a universal challenge across all businesses. When you have authoritarian command and control type leaders, you will have a team that is disengaged, doesn’t have a voice, fear of failure. And we really need to move to a time where leaders back down. Get away from this authoritarian approach, and they start to walk amongst the players. See the players as peers. Ask more questions, do more listening.

Q. Could you tell me the main differences between working with players from this country versus players from other countries?

A. Every country has a unique athletic “DNA” or psychological makeup. While it’s a generalisation, we find that Australians, Indians, and others each have a distinct general psyche. As a coach, the priority is to first understand the players you are working with, and then to see what strategies or techniques from other countries might help them improve.

Traditionally, Indian hockey is very instinctive and individualistic, full of flair. In contrast, teams from countries like Germany, the Netherlands, and Australia are highly structured. While those teams could benefit from more flair, Indian hockey could use more structure and a stronger sense of connection between players. The goal is to enhance the natural flair of Indian hockey with a bit more structure, rather than trying to change its fundamental nature.

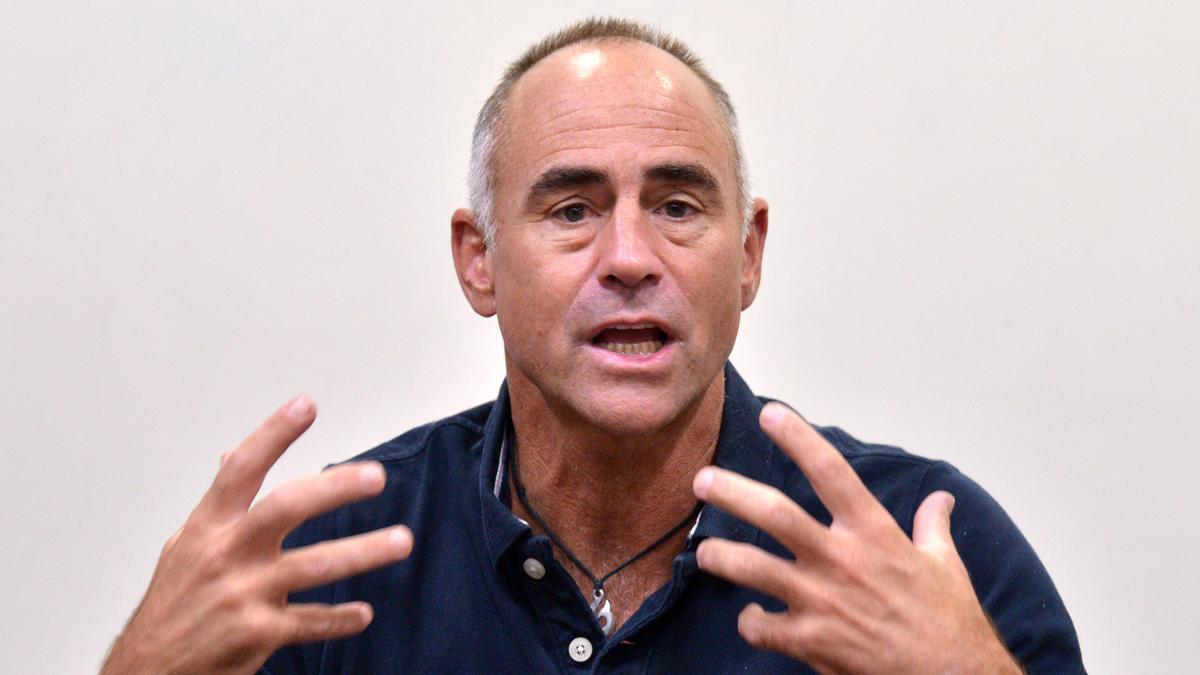

Upton says dealing with pressure is the highest level of mental block because of the importance given to results.

| Photo Credit:

MOORTHY RV/ The Hindu

Upton says dealing with pressure is the highest level of mental block because of the importance given to results.

| Photo Credit:

MOORTHY RV/ The Hindu

Q. In a team sport like hockey, where different players have different positions, a goalkeeper has to guard the goal and is always under scrutiny. So, what kind of exercises do you have goalkeepers do?

A. Yeah, on the surface, it’s easy to recognise that if a striker makes a mistake in the attacking D, it doesn’t get talked about much. However, if a defender gets beaten and a goal is scored, it’s considered their fault. Similarly, if the goalkeeper, who is the last line of defence, makes a mistake, they and the defenders look the worst compared to the attackers.

We try to address this and foster a better understanding within the team. I’ve spent a lot of time on this trip helping players deal with failure because it will happen to every single person. We work to normalise it, to expect it, and to know how to respond when this very natural, normal, and OK thing happens. While it’s not OK to repeat the same mistake two or three times, we are working to truly normalise making a mistake once.

As I mentioned, first, you accept it, then you expect it, and finally, you respond with a solution, letting the mistake go. Your teammates also play a crucial role in this process. Recovering from mistakes is a huge part of any sport, and a lot of teams get this wrong. This presents an opportunity to gain an advantage. The concept of normalising failure is very foreign in India, and not just in sports.

Q. Just touching upon normalising failure, again, a foreign concept in a country like India. How do you communicate that to players?

A. I speak with players, talk to them. A problem is when a family member who is still healthy gets terminal cancer. Like, if you can’t feed your children, that’s a problem. Losing a hockey match? That’s not a problem. Yeah, that’s not ‘Indian-ness’; that’s a first-world problem because this is a first-world environment.

Yeah, that’s perfectly normal. And I mean, we used the example in the lead-up to this tournament of Roger Federer’s recent speech that was so widely spoken about: he only won 54% of the points he played. So, we take that and go, ‘The best in the world has lost 46% of all points he’s played.’ So, if he can make those mistakes or can get beaten, it’s okay for us to make mistakes. So we’ve based it on that.

Published on Sep 03, 2025