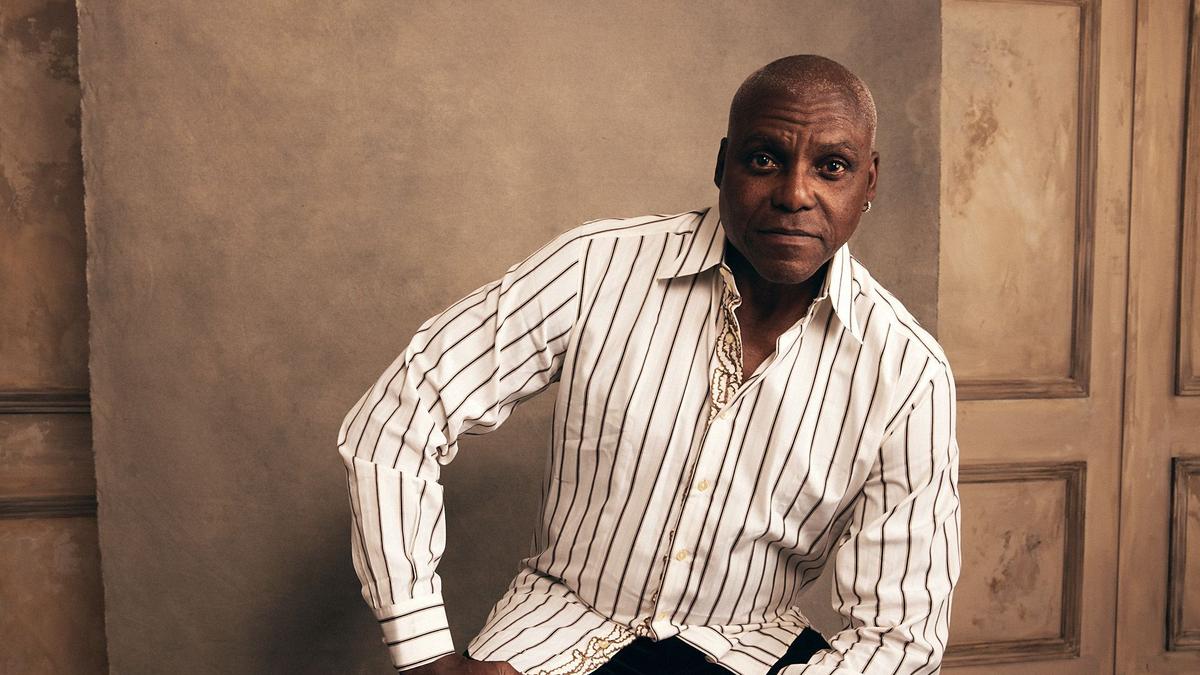

Carl Lewis: “If you have enough likes, enough followers, and if you’re famous, then you’ve ‘won.’ It’s not about excellence anymore”

Things didn’t go so well for Carl Lewis the last time he was at New Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium. Lewis is one of the all-time greats of track and field, with nine Olympic and eight World Championships gold medals. But, during his only competitive appearance in India, at the Nehru Centenary International Athletic Meet in 1989, the jet-lagged American was beaten in the 100m by a little-known Austrian sprinter, Andreas Burger.

His return to the venue earlier this month, as chief guest of the Vedanta New Delhi Half Marathon, was far less stressful. Although the early morning start typical of distance running initially threw him off, Lewis soon hit his stride in a freewheeling chat with Sportstar.

He spoke not only about his previous experience running in India but also about how social media has distorted goals for younger athletes today, his coaching career, the one ambition he never achieved, whether track and field can reclaim the spotlight, and how his life could come full circle at the 2028 Los Angeles Olympics.

What was your experience at the half-marathon like?

It was really interesting because I’ve never been to a race at five o’clock in the morning. That was a challenge! Distance runners run in the morning all the time. Sprinters do not. We cannot! But it was a joy to see the crowds stretching endlessly and to see the happiness in people, especially the young ones.

You don’t have the best memories at JLN, though. A long time ago, you competed here, and the race didn’t go so well for you.

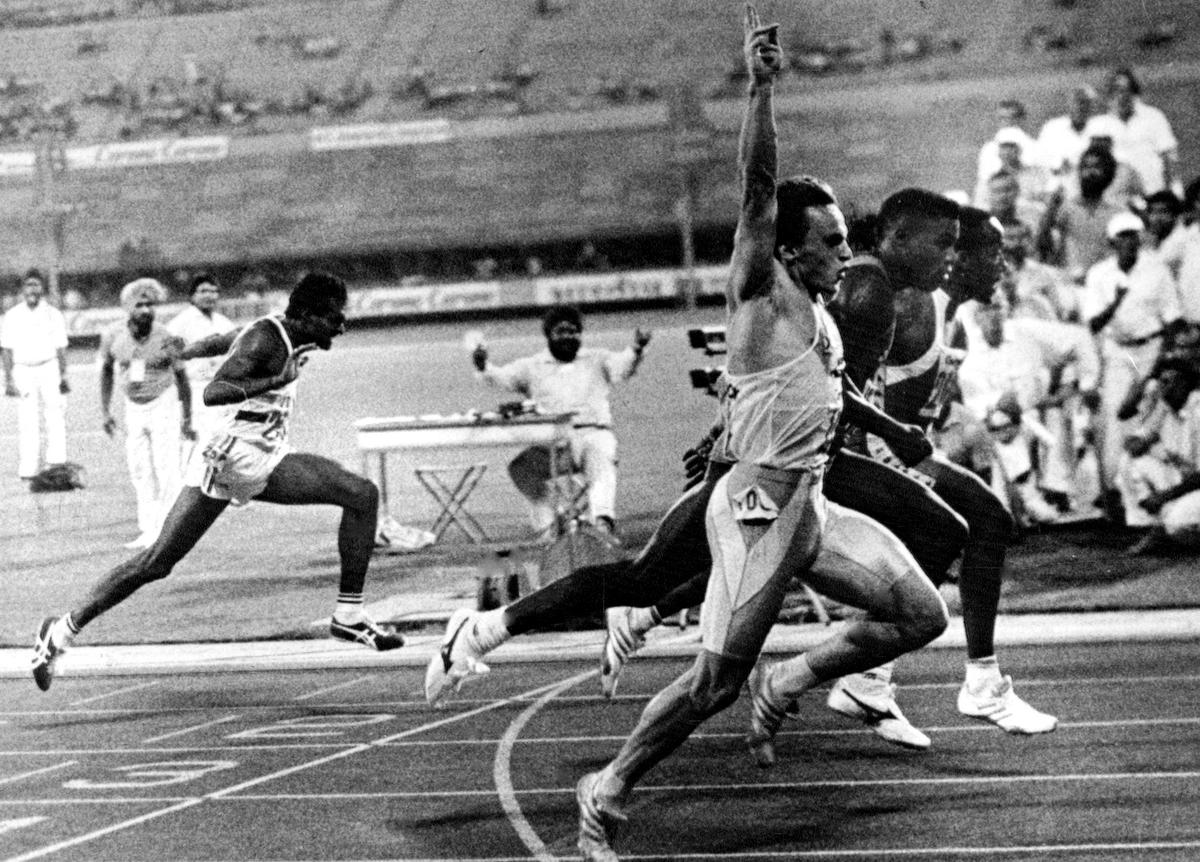

Rare defeat: Andreas Berger celebrates after edging past Carl Lewis by one hundredth of a second to win the 100m on the opening day of the Nehru Centenary International Athletic Meet in New Delhi on September 19, 1989.

| Photo Credit:

HINDU PHOTO LIBRARY

Rare defeat: Andreas Berger celebrates after edging past Carl Lewis by one hundredth of a second to win the 100m on the opening day of the Nehru Centenary International Athletic Meet in New Delhi on September 19, 1989.

| Photo Credit:

HINDU PHOTO LIBRARY

I remember it was late in the year, but yes, it happened. 1989 was kind of in the middle of my career. I didn’t win every race, but I always tried to make sure I won the big ones. I don’t have any sadness about that time. It was an incredible experience to come to India.

After the race, I went and bought this huge bronze sculpture of a religious figure that I tried to take home. Unfortunately, it wouldn’t fit in my luggage, so I placed it on the seat next to mine on the flight home. They even had to buckle it in! I’ve been to India many times. I love the country and the culture, and I’m just glad I was invited in the first place.

How did you process those moments when you did lose? Because there can’t have been many of them.

I wouldn’t say ‘processing’ is the right word. I’d say I evaluated my race. I’d look at what I could do better and ask myself a few questions: What did I do poorly? What mistakes did I make that I could correct? How did I prepare? I always evaluated my races from more of a business standpoint, not an emotional one.

I never gave away emotional control to my competition because that didn’t help. I was always focused on what I could control. That meant thinking to myself, ‘ You didn’t push out of the blocks properly,’ ‘ You didn’t run the turn right,’ and ‘You fouled too many times.’ So I worked on those things.

Is that the kind of obsession needed to be great?

Everyone has their own way, but I was in a unique situation because I did both the jumps and the sprints. In the 30 years since I retired, maybe only a couple of athletes have had success in both. There aren’t many people who’ve been in my situation.

I also don’t think we’ll see it happen again. That’s just how society is now. You won’t see another Jesse Owens, someone excelling in both the sprints and the jumps. I just don’t see it.

It was different for me because I had to do so much more than everyone else in the competition. I was always doing two events a day, so I had to look at things differently.

Golden quartet: Carl Lewis’s 1984 Olympics defined athletic supremacy as he matched Jesse Owens’s 1936 feat with four golds — in the 100m, 200m, long jump and 4x100m relay — setting new Olympic and world records along the way.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Golden quartet: Carl Lewis’s 1984 Olympics defined athletic supremacy as he matched Jesse Owens’s 1936 feat with four golds — in the 100m, 200m, long jump and 4x100m relay — setting new Olympic and world records along the way.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Why do you think athletes these days don’t combine events?

Honestly, the long jump is too difficult for most people. They just give up on it. It’s not that there isn’t talent — there are plenty of great athletes who could do it. But when they reach the next level, they realise, “Man, the sprints are pretty easy compared to that jump.”

I was always a jumper at heart. I loved the event because it was hard. To me, the sprints were the easier part. Since I already enjoyed doing the tougher thing, it allowed me to do both.

I don’t think too many fans would have guessed that. What do you think a lot of fans miss about track and field?

The technical aspect, for sure. When it comes to sprinting, most people can only run at full speed for about one second — so for most of the race, you’re either speeding up or slowing down.

Many people would tell me, ‘You didn’t get a good start.’ And I’d think, no, I had exactly the start I trained to have. I knew that 90 per cent of my race was designed a certain way, and that start was part of the design.

Why do you think jumpers aren’t hitting the same distances as in your generation?

One thing I’m noticing is that jumpers today aren’t having the same kind of success we did. I think they’re jumping differently, and that’s why they’re struggling. I see certain things they’re not doing if they want to go farther.

There are crucial movements in the final three steps of a long jump — small but vital changes in the angle of take-off that allow you to hit the board with more force and speed. It’s a little complicated, but that’s where the distance comes from.

Right now, most long jumpers are in the 8.40m or maybe 8.50m range. That’s solid; they’re good athletes, and they’re working hard. But if you want to jump 8.60m, 8.70m, 8.80m or even 8.90m, there are specific things you need to do differently, and I’m not seeing that.

All-rounder: Carl Lewis competes in the final of the Men’s Long Jump event of the Track and Field competition of the 1984 Olympic Games held on August 6, 1984, in the Los Angeles Coliseum in Los Angeles, California. Lewis won the gold medal.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

All-rounder: Carl Lewis competes in the final of the Men’s Long Jump event of the Track and Field competition of the 1984 Olympic Games held on August 6, 1984, in the Los Angeles Coliseum in Los Angeles, California. Lewis won the gold medal.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

It’s the same on the women’s side. They’re jumping around 7.00m, but if you want to reach 7.30m or 7.40m, there’s something different you have to work on.

I understand what needs to be done, but right now we’re in a space where it’s acceptable to jump 8.40m as long as you get the medal. And, yes, it’s the same Olympic medal I received — I jumped 8.72m in Seoul — but performance is about more than the prize. It’s about you.

It’s not that today’s athletes aren’t good. The long jump is just an event that works against your instincts. You have to fight genetics and fight what your body is telling you not to do to perform it correctly. We’re not designed to jump forward; our bodies are built to jump vertically, not horizontally. If you try to leap over something, you often feel like you’re going to fall forward. That’s a safety mechanism. So to jump really far, you have to override that instinct, and that’s something a lot of people don’t yet understand.

Right now, there are only a few people alive who have truly mastered that: Mike Powell, myself, Larry Myricks, and a few others. I coach college kids now, and some of them compete around the world. But even then, I don’t always see the desire to figure it out, because they’re still winning.

Why do you think that is?

We live in a society that no longer rewards or even values the excellence of performance. We’re too focused on the prize. That’s what social media has done to us; it doesn’t matter what you actually achieve. If you have enough likes, enough followers, and if you’re famous, then you’ve “won”. It’s not about excellence anymore.

You won a whole lot of medals, too! What motivated you then? You usually get motivated if you don’t have something, after all.

Gold restored: Final of the men’s 100m at the 1988 Seoul Olympics — a race that shook the world. Ben Johnson crossed first, but after his steroid scandal, Carl Lewis was crowned champion, with Linford Christie and Calvin Smith moving up the podium.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Gold restored: Final of the men’s 100m at the 1988 Seoul Olympics — a race that shook the world. Ben Johnson crossed first, but after his steroid scandal, Carl Lewis was crowned champion, with Linford Christie and Calvin Smith moving up the podium.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

It depends on what you want to achieve. I wanted to jump 8.90m — to match Bob Beamon. So, I kept jumping, trying to reach that mark. I was always motivated because I only came close once. That goal stayed with me.

In the sprints, I wanted to run faster, to break the world record. When I ran 9.93 for the world record, the next goal became 9.8. I always had a goal, and it wasn’t about winning or being number one. It was about the performance, about achieving what I knew I was capable of.

The big thing is that I always jumped and ran for time and distance, not for place. What disappoints me about today’s jumpers is that many aren’t trying to jump farther. They’re content with mediocrity.

And I wish they weren’t, because they have the talent. They work hard; they do everything right. But there isn’t a single jumper in the world saying, ‘I want to break Carl Lewis’s record. I want to break Mike Powell’s record.’ That’s my frustration. They’re great athletes and great kids, but when I was 17, I said, ‘I want to break Bob Beamon’s world record’. It took me until I was 30 to do it, but that was my goal from the start.

Right now, I don’t see anyone interested in breaking our records — they’re satisfied with winning medals. It’s not a lack of ability; it’s cultural. Performance doesn’t matter as much as winning. When the culture rewards you for being famous rather than being excellent, you start thinking, “Hey, I’m still winning medals — that’s enough.”

Are there any goals you wish you could have accomplished?

Of course! The long jump world record that Mike Powell holds. I never got that one. That’s probably the only thing. I love Mike; we actually talk about it a lot. I have a lot of respect for him.

He was a great competitor and a great guy. We still see each other from time to time. The one thing he has over me is that record. And I’ll say this — that day was the best jumping I ever did, and Mike beat me at the end of it. I can’t say he got lucky or that I might have won on another day.

No, that was the best day I ever had. I gave him my best shot, and he still won. I take pride in the fact that he had to break the world record just to beat me. And I don’t think I’ll see anyone break that record in my lifetime.

And thank God, Mike was so good that I don’t think anyone ever will.

You’re a coach now. (Lewis is the athletics coach at his alma mater, the University of Houston.) What’s that like?

Last year, we had two athletes on our track team who won Olympic medals — a silver and a bronze. That’s the happiest I’ve ever been because I know I helped them fulfil their lifetime goals.

It’s probably interesting for you as a coach because you get to see that transformation in an athlete. Do you remember when you first realised, maybe at 12 or 13, that you weren’t just fast but special?

Actually, it was a lot later — when I was 17. I was a late bloomer. When I was 13 or 14, I was just an average kid. At 17, I suddenly realised, Wow, I have a talent! That’s when I had a growth spurt.

I’d been running for years and had good technique, but I was small. I never thought I’d grow tall — and then suddenly I did. That made all the difference. Some kids develop really young; others much later. If you look at photos of me at 14 or 15, I look like a 12-year-old. Even at 16 or 17, I looked very young for my age.

Do you think it’s possible to build a champion by doing the same things you did when you were young? Or would the process have to evolve completely?

There were great champions then and great champions now. The mindset is just different. Social media is different; the internet is different. It doesn’t make things worse — just different.

But while some things change, the science doesn’t. The ideal running mechanics are the same as they’ve been for hundreds of thousands of years. The best way to run hasn’t changed. The problem now is that everyone wants to prove they’re smarter than the past.

That’s a big issue. There are very few checks and balances, especially in our sport. The internet is full of misinformation. When I go online, I see coaches and so-called experts talking — and at least 90 per cent of it is incorrect.

Everyone wants to be famous and promote themselves, not realising that the best coaches and the best programmes are usually promoted by others. If you’re constantly promoting yourself, you’re probably more focused on promotion than on actually doing the work.

You were one of the greatest as an athlete. How would you rate yourself as a coach?

I can’t answer that — ratings have to come from someone else. But I was lucky because I had the greatest mentor. When I started as a volunteer, I went to coach (Tom) Tellez, and he guided me into coaching. I did a lot of studying. He gave me a stack of papers this high and told me to go read. So I read through everything, absorbed the information, and learned the science behind it. Coach Tellez and I even wrote a book about the science of running. I studied and then put that knowledge into practice. Coach Tellez would watch the sessions and say, “This is right; that’s wrong.” It wasn’t like I just decided to start coaching. I actually put in the time. I couldn’t simply say, ‘I’m Carl Lewis — I know what I’m talking about!’

Why did you feel the need to do that? After all, you are Carl Lewis!

The bottom line is that my name brings both opportunities and challenges. It’s definitely an advantage, and wherever my name can help, I use it. But when it comes to athletics, I had to put in the work. I don’t shy away from that.

Is there a medal that stands out for you?

A few. My first Olympic medal stands out, as does my 100m gold at the Tokyo World Championships. And, finally, my last Olympic medal in Atlanta — those three mean the most. But I’ve donated all my medals to the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., so anyone can see them. I don’t keep any at home. I did that because I understand the power of an Olympic medal. When people see it, they melt.

Last year, one of our University of Houston athletes — Shawn Maswanganyi — brought his medal to campus and showed it to the university president. She held it with such pride. That’s what I wanted for my medals, too. If they sit in my house, no one gets to share that magic. I also have a granddaughter. One day, when I’m gone, I want her, or her children, to be able to go to the museum and say, ‘That’s my papa.’

What does being called the greatest ever mean to you?

It’s funny because people say, “You’re one of the greatest athletes of all time,” and billions may know you or love you. But I still have to shave. I still have to watch what I eat. I still have to exercise. Every morning, when the alarm goes off, I still think, Oh man, I don’t want to get out of bed. It reminds me that I’m just like everyone else, whether I was one of the greatest or not.

It’s interesting that you mention the mundane things, because there must have come a time when age started catching up. How did you deal with that?

I always knew it was coming. I was never afraid of that phase of life, and I wasn’t going to compete once I couldn’t be competitive. I didn’t want to drag my career on.

After Atlanta, I think I could have gone all the way to Sydney. I really do. Maybe not definitely, but I think I could have won at 39. Still, I knew it was time to move on. My life was expanding in other ways, and that’s probably why that transition didn’t bother me.

You competed in an era full of incredible rivalries — Ben Johnson, Mike Powell. What did that competition mean to you?

Competition was vital. My focus was always on running the best race in my lane. The rivalries inspired me to work harder and to stay in front.

You also had a reputation for arrogance. How much of that was real, and how much was performance psychology?

The long jump world record that Mike Powell holds. I never got that one. That’s probably the only thing. I love Mike; we actually talk about it a lot. I have a lot of respect for him — Carl Lewis

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

The long jump world record that Mike Powell holds. I never got that one. That’s probably the only thing. I love Mike; we actually talk about it a lot. I have a lot of respect for him — Carl Lewis

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

You build your confidence; you prepare for it. When I went into major Championships, I was always ready — that’s where my confidence came from. It came from preparation, hard work, and making sure every detail was covered.

I ran a lot of events, but the Championships mattered most. I competed in four World Championships and four Olympic Games. In 1993, I was in a car accident, so I wasn’t at 100 per cent. But even then, I made the 100m and 200m finals. I didn’t do the long jump because of the injury, but I was still ready. I also got sick with Giardia in 1994, so 1995 was difficult. But I knew I could still perform. I told myself, ‘I’m going to give it one more shot — and then I’m done.’

Do you see any part of yourself in today’s athletes?

From a personality perspective, I see a little bit of myself in Noah Lyles. I understand him. I understand that he’s trying to market and brand himself. Of all the athletes in the world today, I probably see the most of myself in him.

If you could go back in time and meet the 17-year-old Carl Lewis, what would you tell him?

I’d tell him the same thing I tell all the young athletes I coach: Listen.

You have two ears and one mouth — listen more. Your elders know a lot more than you think they do.

The Olympics are coming back to Los Angeles. What’s that going to be like?

I think the Games are going to be fabulous. The Olympics bring people together. Paris was incredible, and L.A. will be the same. I’m really looking forward to taking some of our young athletes there. I don’t know what it will feel like walking into the Coliseum with one of them, watching them run their rounds. My role has changed — it’s like being a parent. One day, you realise you’ve become the adult guiding someone else. It will be very emotional.

The last time the Olympics were in L.A., there was the Soviet boycott. Now there’s political division at home — Trump, the culture wars. Do you see parallels?

Honestly, I don’t think America is any more divided than it’s always been. The difference is that this administration allowed people to say things openly. People feel free to be evil, racist, and ignorant. But this country has always been divided — by race and by gender.

The racism and misogyny were always there. What’s changed is that now, under Trump, people feel permitted to say these things publicly.

But you know what? I’m a Black man — this is the life I’ve always lived. So now people around the world say, “This is terrible!” Well, this has always been our reality.

In a strange way, maybe it’s not entirely bad that people say these things out loud now. Because once you’re out, you can’t go back in.

L.A. will probably be important for track and field, too. Back when you were at your peak, the sport was everywhere. Now it doesn’t have the same cultural dominance. How do you fix that?

Unfortunately, I don’t think we can. In the 1980s and ’90s, we fought hard to make the sport professional. Then, in the 2000s, people thought the job was done — and they took their foot off the gas. Other sports have passed us by. I don’t think we’re going back to those glory days. In many ways, we’ve regressed. Athletes make less money now than we did in the 1990s. They have less power and less control. It’s almost like the old amateur era again.

To recover, athletes would have to do a lot of work. Some are starting to realise the sport’s in trouble — but what are they going to do about it? I don’t think enough people have the stomach for that fight.

The best thing we can do now is hold on to what we have.

Published on Oct 23, 2025