Ali vs Foreman: ‘Rumble in the Jungle’ remembered after 50 years

Alfred Mamba was just 12 when boxing great Muhammad Ali descended on Kinshasa, at that time the capital of Zaire, in October 1974 in a bid to regain his heavyweight title.

Mamba watched as his father — a boxing referee — helped carry flags into the arena ahead of the fight between Ali and fellow-American George Foreman in the early hours of October 30.

The memory of the event, better known as The Rumble in the Jungle, has stayed with him for 50 years.

“It was an impossible atmosphere, we have never seen an atmosphere like it,” he excitedly tells AFP on the sidelines of the amateur Africa Boxing Championships in Kinshasa.

The Rumble in the Jungle, which inspired Norman Mailer’s book “The Fight” and the Oscar-winning documentary “When We Were Kings”, has passed into boxing myth.

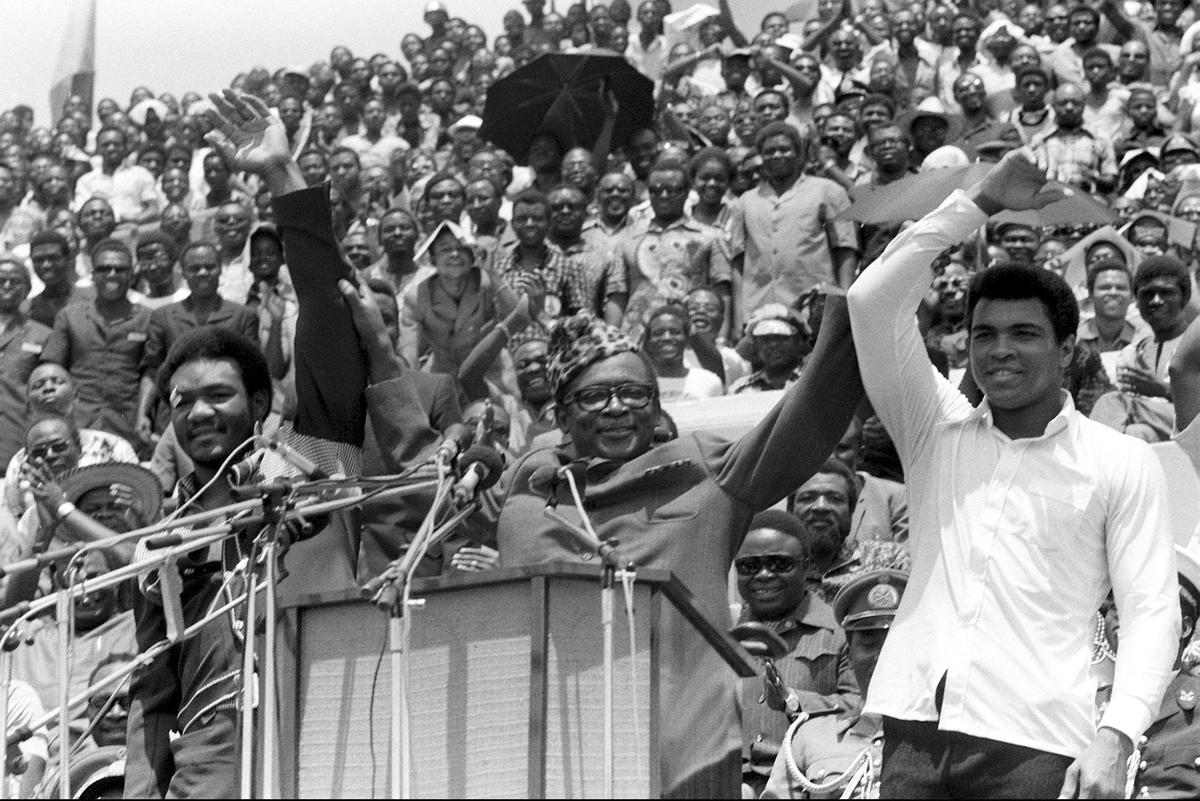

Financed as a big public relations event by Zaire’s dictator Mobutu Sese Seko, the fight took place in the 20th May Stadium, now called the Tata Raphael Stadium and was screened in over 100 countries.

The giant concrete structure was packed to the rafters with some 60,000 spectators, singing, dancing and chanting in anticipation of the match.

’Screaming’

“People were screaming at every possible moment, it was really great,” Mamba recalls wide-eyed.

READ | Nikhat Zareen aims to bounce back from Paris 2024 Olympics disappointment

As he speaks he flicks through black and white paper photos from the legendary event that would turn the tide on Ali’s career.

Foreman, an Olympic gold-medallist at the 1968 Mexico Olympics, was the favourite – the 25-year-old had won his first 37 fights after turning professional.

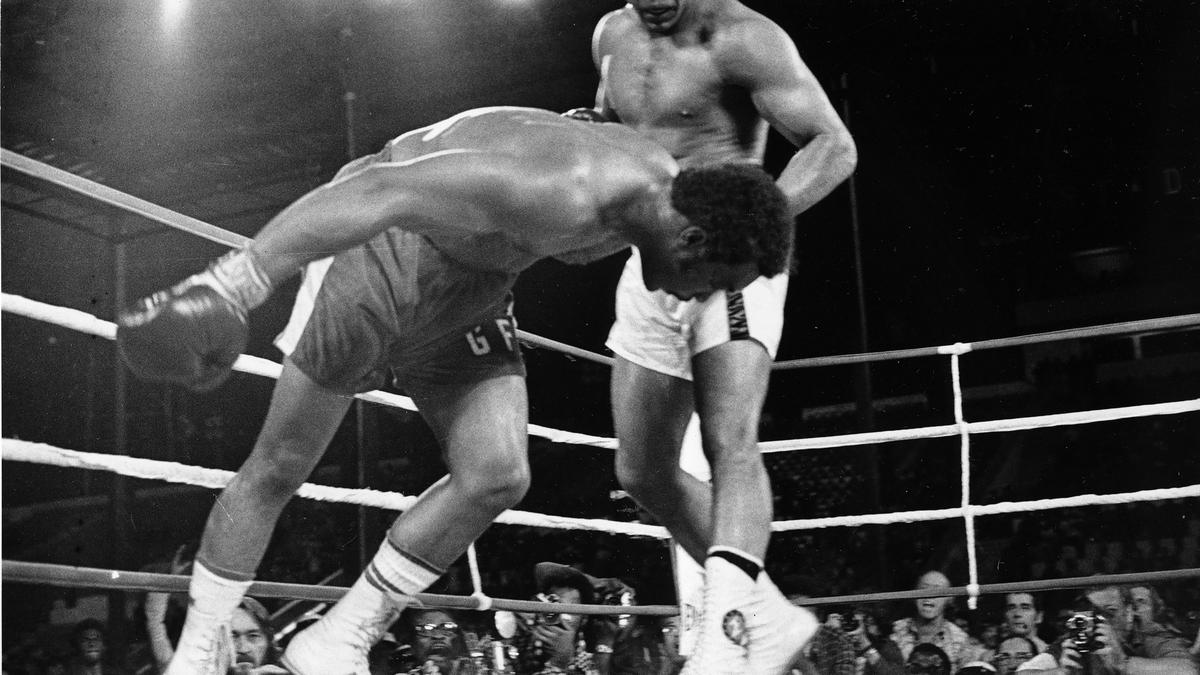

He started out the stronger but Ali, now 32 and employing his famous rope-a-dope tactics, turned the tables and landed a left hook and straight right that sent Foreman to the canvas in the eighth round.

Foreman tried to get to his feet but the referee signalled the end of the fight and a knockout win for Ali.

It was a triumph for Ali who reclaimed the title that had been stripped from him in 1967 when his decision to refuse the draft to fight in the Vietnam War landed him a three and a half year suspension.

“People really wanted Muhammad Ali to win the fight,” says Mamba.

There was no clear reason why the locals leaned in his favour but, according to magazine The Africa Report, Ali created one.

When Foreman arrived in Zaire – now the Democratic Republic of Congo – with his two German Shepherd dogs, a breed favoured by the Belgian colonialists, Ali said Foreman was a Belgian, and the crowd backed him.

“When Muhammad Ali gave the (final) punch everyone screamed,” says Mamba.

‘Ali was Congolese’

Martin Diabintu, also a referee in the amateur boxing competition in Kinshasa, tells AFP that the locals considered Ali “like a brother”.

“Ali was Congolese,” he says simply.

File photo of Zaire’s President Mobutu Sese Seko (center) as he raises the arms of heavyweight champ George Foreman )left) and Muhammad Ali (right)

| Photo Credit:

AP

File photo of Zaire’s President Mobutu Sese Seko (center) as he raises the arms of heavyweight champ George Foreman )left) and Muhammad Ali (right)

| Photo Credit:

AP

The fight was due to take place on September 25 but had to be delayed after Foreman suffered a cut in training.

That only cranked up the anticipation around the world and, more particularly, in Kinshasa.

“Everyone wanted to see this fight, everyone wanted to assist in the fight,” says Mamba.

Boniface Tshingala, another referee at the amateur boxing competition alongside Mamba and Diabintu remembers people queueing for kilometres outside the stadium.

Hours before the fight started “there were people massed around the stadium from all four corners of the capital,” says Tshingala.

“Outside the stadium it was full to bursting. Everyone wanted to come in.”

Tata Raphael Stadium, which has since hosted sporting events including the Francophone Games in 2023, has been updated somewhat in the half-century since The Rumble but the memories remain vivid.

“We commemorate the fight even today,” says Diabintu, who was also a former boxer. “We call it ‘the fight of the century’.”

Now 64, Diabintu was just a teenager when Ali and Foreman came to Kinshasa. He was so eager to watch the fight he walked 10 kilometres (six miles) from his home to the stadium.

“I came on foot. After I finished school I came to see the combat,” he says.

As well as exciting his curiosity the event had an even greater impact on his life as he progressed from boxer to coach to referee.

“It’s this event that pushed me into boxing.”

All three former boxers describe pride at the DRC having hosted the event that still resonates fifty years later.

“People didn’t believe that DRC could organise this fight (but) we succeeded 100 percent,” says Mamba proudly.