One small centimetre for man, a giant leap for Armand Duplantis

No medals are awarded at the Diamond League competition in track-and-field, but a day before the Silesia Diamond League competition in August, organisers announced an award for the most valuable athlete of the meet, as judged by the World Athletics points system. At the customary pre-competition press conference, they displayed a sparkling 14-carat gold diamond-encrusted ‘Champion Ring’ worth $10,000, along with a cheque for the same amount.

On a sweltering August afternoon at the Silesian stadium the next day, it had seemed that that ring was going to be firmly on the finger of Jakob Ingebrigtsen. The Norwegian shattered one of the longest-standing track world records, clocking a staggering 7:17.55 for the 3000m, taking more than three seconds off the mark of 7:20.67 set by Kenya’s Daniel Komen in 1996. It was one of the most remarkable moments in track and field history.

But it wasn’t the most remarkable event of that day. Because Armand Duplantis was also competing.

Read | The night Mondo Duplantis fulfilled his childhood fantasy

He had already started the men’s pole vault competition while Ingebrigtsen was running. Ten other athletes were competing. By the time he had casually attempted his second jump — to seal his place in the top three, his competitors had gone through 64 of their own. The next three made another 13 jumps, while Duplantis went on top with a single clearance at six metres. Two jumpers cleared six metres — the first time in history that three pole vaulters have crossed six metres in a single competition. But while Sam Kendricks and Emmanouil Karalis have done all they could, Duplantis is just getting started. From here on, his competition is with himself. Almost casually, Duplantis set the bar up at 6.26 metres — 1 centimetre higher than the world record he himself had set less than a month before at the Paris Olympics.

Armand Duplantis operates in a hemisphere of his own.

| Photo Credit:

Pranay Rajiv

Armand Duplantis operates in a hemisphere of his own.

| Photo Credit:

Pranay Rajiv

At the Stade de Paris, amidst the ecstatic cheers of 40,000 spectators and the applause of his competitors, Duplantis had cleared the height. After landing on the mat, he sprinted off to celebrate with family and friends. Earlier, he had marked his Olympic Record achievement with a finger-pistol salute for the cameras, inspired by Turkish shooter and Paris Olympics silver medallist Yusuf Dikec.

In Silesia, Duplantis follows a nearly identical routine. He charges down the runway with incredible speed, holding his pole high above his head to maximize the energy needed to bend the fibreglass instrument. His plant is near perfect, transferring the energy efficiently into his swing. Without hesitation, he inverts himself completely until he is almost vertical above the ground. Each step gains him crucial inches, and as he turns his body at the peak of the movement, he ensures he retains every bit of height.

Smashing records: Armand ‘Mondo’ Duplantis cleared a height of 6.26 metres at the Silesia Diamond League meet to break the pole vault world record again.

| Photo Credit:

AFP

Smashing records: Armand ‘Mondo’ Duplantis cleared a height of 6.26 metres at the Silesia Diamond League meet to break the pole vault world record again.

| Photo Credit:

AFP

When he lands on the mat, it seems Duplantis doesn’t really know how to celebrate the new world record. He high-fives the mascot, then runs past a gaggle of photographers before lying down on the track.

When you are Duplantis, though, this makes sense. Just how many different celebrations can you come up with, even if for a new world record?

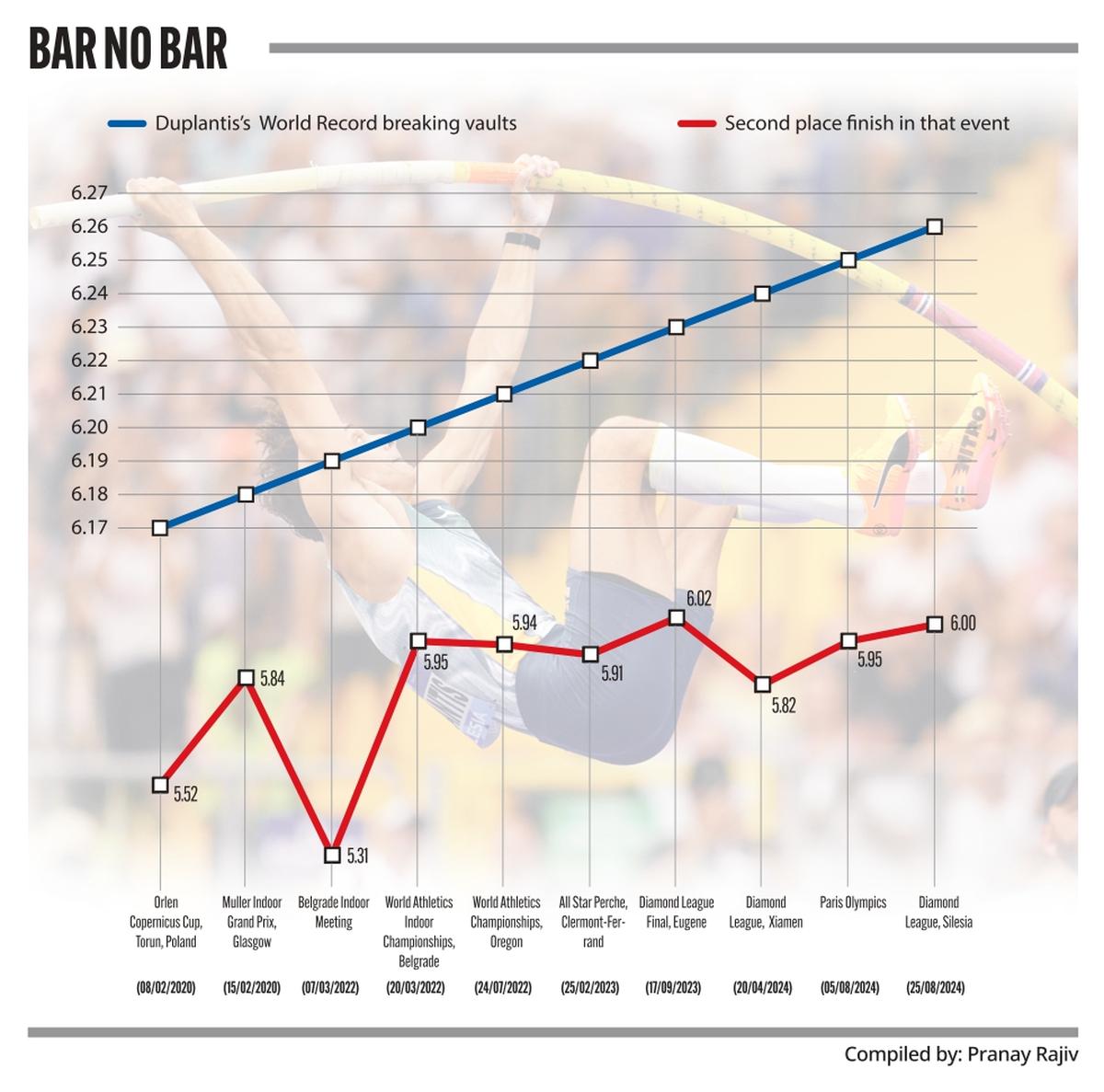

Duplantis should probably practise a few options for the future. When he enters an event now, his only real competition is with himself. What else can you expect from the man who has broken the world record 10 times over the last four years.

In fact, Duplantis is so good at his event that it actually pays him not to give his 100 per cent every time he competes. Track-and-field athletes receive an additional bonus each time they break the world record. The caveat is that you only get the prize money one time at the meet you broke it at. So, each meet, Duplantis raises the bar just one tiny centimetre. And each meet, he earns another bonus. That’s why when you scroll the ‘All Time Top Lists’ section of the men’s pole vault event on the World Athletics statistics page, you’d have to scroll all the way to No. 11 to see someone not named Armand Duplantis.

That level of dominance that’s almost unheard of in track-and-field. The last athlete to have anything similar was Ukrainian great Sergey Bubka, who broke the pole vault record 35 times. But Bubka topped off at 6.15 metres. Duplantis has equalled or gone past that mark 13 times already. Indeed, of the top 101 jumps of all time in the pole vault event (6.02 m and above), Duplantis (6.26) has 44 of those; everyone else combined has 57.

Duplantis seems like even more of a statistical anomaly when you compare his world record to the next best in his sport. The next highest vaulter after Duplantis is France’s Reynaud Lavillenie, who jumped 6.16m in 2014. So, Duplantis’ record is 1.623% better than the next best vaulter ever. For perspective, Usain Bolt’s world record in the 100m is 1.15% better than number two, Tyson Gay. Ingebrigtsen, who smashed the 20-year-old world record in the 3000m in Silesia, is 0.71 per cent faster than the next best runner over the same distance.

So what makes Duplantis so good?

He’s that rare combination of nature and nurture. Most athletes come into the pole vault — perhaps one of the most technically challenging events in track-and-field — relatively late in their development. That isn’t true for Duplantis. The child of an elite jumper (Greg Duplantis had a PB of 5.80m) and an international heptathlete (Helena Duplantis) — Mondo — or Armand as he was originally named has been practising on the home-built pole vault pit in his family backyard in South Louisiana since the time he was six. Even though he’s just 24, he already has the level of technical experience of someone many years older.

Duplantis was someone who was almost destined to be a pole vaulter. Speaking to Athletics Weekly, Scott Simpson, a former Olympic medal-winning coach, spoke of the jumper’s almost manic obsession with the sport. “I’ve heard them (Mondo’s parents) tell stories about having to go to his room and drag him off YouTube at midnight when he was watching pole vault videos! He has had an obsession with it and that competitiveness, irrespective of what he’s doing. That creates a mindset that is very difficult to beat. When he doesn’t do as well as he would like, you can see that frustration in him, which is fascinating to watch,” Simpson says.

And then there are the technical bits. At the Paris Olympics, American Sam Kendricks, who took silver in the pole vault, said Duplantis “had the hand of God behind him.” He was referring to Duplantis’s incredible speed on the runway, which allows him to put in incredible energy to bend the pole.

Kendricks isn’t just speaking in hyperbole. As a schoolboy, Duplantis had a 100m personal best of 10.54 seconds, and in a couple of weeks he will be taking on 400m hurdles Olympic gold medallist Karsten Warholm in an exhibition 100m race.

“Mondo’s speed on the runway is almost unprecedented,” Simpson told Athletics Weekly. “The speed that he puts into the takeoff at the end of the approach run is higher than we have seen from anybody else previously. The more speed you have, the higher the amount of energy you have available to you. Pole vault is an energy storage game. You store energy in the pole as it bends, and the more energy you can store in that pole, the more energy there is that can be returned to you to propel you into the air at the end of the jump,” he said.

“In addition, the guys that have had good speed at takeoff typically don’t complement it with on-pole technique, which is as good as the slower guys, but Mondo manages to do both. He puts a lot of speed through the take-off point but also has incredible on-pole abilities for the speed at which everything is happening — something that is quite unique to him. He is also so consistent. He has this huge toolbox that he has built up from doing pole vault from such a young age, which enables him to produce a really consistent output. Regardless of whether there’s wind, rain, high pressure, a competitive environment, or him jumping on his own, it doesn’t seem to matter because he still produces this incredible output and leaves him head and shoulders above everyone else,” Simpson says.

For now, Duplantis is so far ahead of the rest of the field, he can continue to break the world record one centimetre at a time. But just how far can he go? Is the sky really the limit for him?

Owning the moment: Duplantis celebrated for the cameras with a finger-pistol salute, inspired by Turkish shooter and Paris Olympics silver medallist Yusuf Dikec.

| Photo Credit:

Reuters

Owning the moment: Duplantis celebrated for the cameras with a finger-pistol salute, inspired by Turkish shooter and Paris Olympics silver medallist Yusuf Dikec.

| Photo Credit:

Reuters

As easy as he makes it seem, the fact is that the higher Duplantis goes, the harder it gets to get even that one centimetre of height. Duplantis reflects on its scale: “It’s so marginal, but makes more of a difference than you can imagine,” he says. “Even if it’s one centimetre, it gets to a certain point where you hit it and it suddenly becomes so much more difficult.”

The fact that he’s literally in a league of his own means Duplantis ends up having to compete in two separate competitions — having to beat everyone else first, then getting to target the world record. Whereas others might build up from their competition-winning height to the world record, Duplantis has no option but to go straight for it. This completely flips the physical and mental demands. Just like in Silesia, he has to make a couple of jumps while the rest of the field does their things, and then all of a sudden, he will have to be prepared to jump higher in quick succession.

But as his jumps in Silesia and in Paris earlier this year have shown, there’s still a lot of height left in him. At both competitions, Duplantis failed his first attempt at the world record, not because he didn’t clear the height but because he landed on them on the way down. When he did clear the height successfully, there were several inches between his chest and the bar on the downward journey.

“I don’t think he’s at his peak right now. He’s only 24, and pole vaulters typically peak in their late 20s to early 30s,” coach and father Greg told Red Bull.com. “He’s still getting stronger, and I think he’s going to be better in four years than he is now. He’s already jumping higher than anyone ever has, and to predict how high he can jump is crazy. This probably does sound crazy, but I think he can get close to 6.40 m. If not 6.40m. But it will require a lot of work.”

That mark may be several years into the future. There are going to be a lot of shiny rings and shinier medals for Duplantis to collect until then.