100 years of Indian hockey — A mother’s medal, a daughter’s dream: Inside the Siwach hockey story

Twenty-year-old centre forward Kanika Siwach is one of the mainstays of the Indian junior hockey team, just as her mother, Pritam Siwach, was for the Indian team of the 1990s and 2000s. But if Pritam has her way, there will be more generations of Siwaches playing hockey for India.

When she joined the Indian junior women’s hockey camp in Bengaluru, Kanika decorated the wall of her hostel room with a collage of posters. That in itself isn’t unusual, since many of her teammates have pictures of players they admire and hope to emulate. But Kanika didn’t have to look far for motivation. The photographs and magazine pull-outs on her wall are of her own mother, former India international and 2002 Commonwealth Games gold medallist Pritam.

“I put it up so that I can get inspired by them whenever I see it. I get inspired every day. If I’m feeling low, I remember whose daughter I am and whose blood flows in me. If she could do it, so can I,” says Kanika, who is preparing for the Junior Women’s Hockey World Cup in December this year.

And if the pictures aren’t enough, Pritam is only a phone call away. “We speak every night. Sometimes we discuss hockey, but at other times we simply share our thoughts. We have always been very close. Kanika was born when I was 30, and I was playing international hockey until I was 32, and departmental hockey until much later. When she was very young, I would take her everywhere I went,” says Pritam.

With a mother who was a decorated international and is now one of India’s most successful coaches (three members of the Indian women’s squad that played at the Paris Olympics were trained by Pritam, a Dronacharya Award winner, at her academy in Sonipat), it might have seemed inevitable that Kanika would take up hockey.

But that wasn’t a given.

India indeed has its share of multi-generational hockey families. Pritam’s son, Yashdeep, has already represented the country internationally. But Pritam and Kanika are among the rare mother-daughter duos to have represented India at any level. Should Kanika eventually earn a senior cap, as many expect, they would become the first mother and daughter to play for the senior national team.

A lot of that has to do with culture, says Pritam. “I think the difference, why there are next to no mother-daughter generations in Indian hockey, is that many women raise their children, especially their daughters, very protectively. They think of all the struggles they had to go through and don’t want their daughters to face the same,” she says. “It comes down to how brave you are and how much trust and confidence you have in your daughter. It’s not easy in India. If you’ve been an elite player, chances are you could provide an easier path for your children. You might think, ‘Okay, I’ll make them study, get them married well, and ensure a good job in the private sector.’”

That, Pritam feels, limits what girls can achieve. “In choosing this safer path, we forget that our daughters have to be happy. I always wanted my daughter to play. Sport made me happy. I want my daughter to experience that as well,” she says.

Inspiring legacy: On her hostel wall, Kanika has pasted pictures of her mother, whose journey in Indian hockey keeps her inspired every day.

| Photo Credit:

SPECIAL ARRANGEMENT

Inspiring legacy: On her hostel wall, Kanika has pasted pictures of her mother, whose journey in Indian hockey keeps her inspired every day.

| Photo Credit:

SPECIAL ARRANGEMENT

Kanika says she was never pressured into the sport. “I grew up playing everything. Initially, I didn’t even care much about hockey. At home, everyone played hockey — my father, mother and brother. During dinner, everyone would constantly talk about it. At that time, I didn’t like it because I couldn’t understand what they were talking about. But eventually I started playing and found out that I liked it,” she says.

Although her mother was a respected player and coach, Kanika insists she didn’t get any special treatment. “Nothing was made easy for me. In fact, I felt my mother was extra strict with me because she never wanted to be accused of favouritism. When I was in Class 6, I went for my first competition outside Sonipat. We stayed in a government school where we slept on the bare floor on bedsheets. The washrooms were dirty. I had never experienced anything like that, so I called my mother and asked how I could stay there. She told me, ‘Stay like the rest of your teammates are,’” Kanika says.

Pritam remembers that moment vividly. “I knew those were the facilities you get playing hockey in India. If I tried to protect her, then she would never learn to accept it. She wouldn’t get the toughness she needed to survive as an Indian hockey player,” she says.

High standards

The tough love, Kanika admits, may have been necessary. “Everyone thinks it’s easy for me because everything was charted out for me. But it’s hard growing up with a lot of eyes on you. There’s constant pressure and expectation. I always feel I have to perform twice as well to justify my place,” she says.

Those high standards haven’t faded even though Kanika is now one of the pillars of the junior team. “She’s proud of me but keeps telling me I need to work harder. She says it’s not enough to just be part of the team or go to a World Cup — I have to win a medal too. She keeps pushing me,” Kanika says.

Try as she might, Pritam admits it’s hard for Kanika to develop the same mindset she once had. “I can’t expect Kanika to be as mentally tough as I was. We’re playing in two very different generations. When I started, there was little media support or exposure. We had to fight not just on the field, but at home and in the village for the chance to play. I got married very young and had both my children during my career. Now things are far more professional. There are leagues, and players are better off financially. I sometimes tell her that no matter how bad things get for her, players from my time had to pick up women’s hockey from zero,” she says.

Kanika, Pritam says with a smile, is a lot softer. “Kanika plays the same centre-forward position I did, so I can compare us. She’s physically stronger than I was at her age and uses that strength well. She’s quick with the ball and always looking for chances to score. I used to keep my head down too much. But for all her skill, she isn’t as tough mentally. She cries quickly! Her heart is a little weak. I was more of a fighter because I had no choice. If I’d been even a little weaker, I wouldn’t have gone anywhere,” she says.

Harder workers

Pritam believes players of her generation valued opportunity differently. “Getting a chance to play was a blessing, so we took it more seriously. Players today get more exposure and better facilities, which is great. But maybe we were more dedicated. We constantly worked on our personal technique. What I notice as a coach now is that players rarely do anything beyond their regular training sessions,” she says.

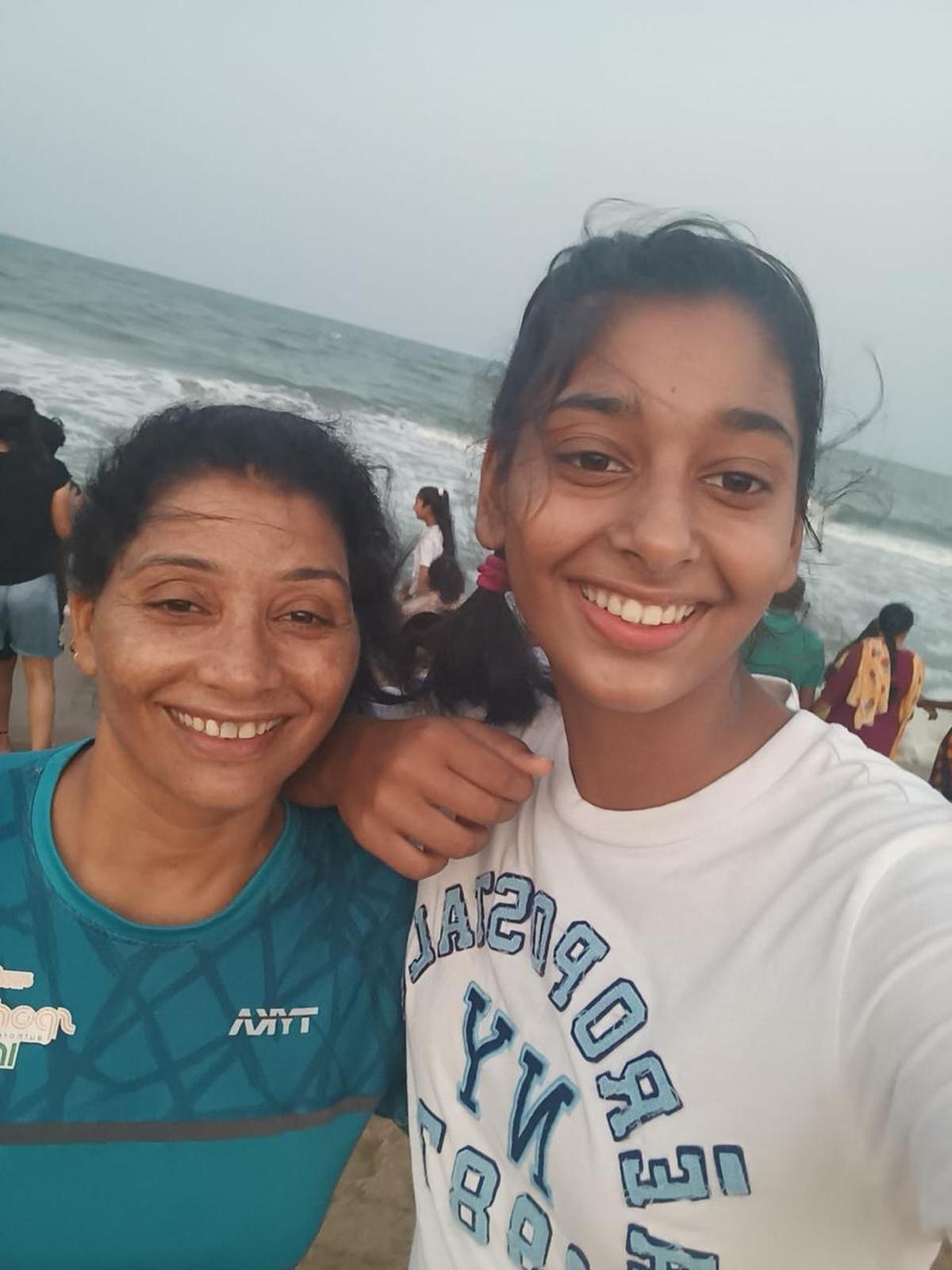

Beyond hockey: Away from the turf and competition, Pritam and Kanika share a quiet moment by the sea, simply mother and daughter.

| Photo Credit:

SPECIAL ARRANGEMENT

Beyond hockey: Away from the turf and competition, Pritam and Kanika share a quiet moment by the sea, simply mother and daughter.

| Photo Credit:

SPECIAL ARRANGEMENT

Kanika agrees but says her mother’s discipline drives her. “I don’t think I’ve seen anyone as dedicated to hockey as her. Even after retiring from international hockey, she played departmental matches for years. One day, a friend called to say, ‘Do you know your mom just made a full-length dive and scored a goal?’ I was shocked! I’d heard stories of her comeback after having me — when people thought she’d slowed down, she challenged the fastest girl in the team to a race and beat her. Even now, when we play each other, she’s really tough to beat. That’s the fighting spirit I want,” says Kanika.

Bigger dreams

Mother and daughter differ not only in temperament but also in ambition. Kanika’s dream is to play in the Los Angeles Olympics three years from now. For Pritam, the Olympics remained a dream unfulfilled.

“It’s always the case that every new generation builds on the previous one. For me, the Olympics were something I could never compete in. When I was young, I didn’t even know about them. My goal was simply to play for India. For Kanika, the Olympics feel possible. She’ll have to work very hard, but I’m happy she’s aiming that high,” she says. That sense of continuity is how Pritam sees her own mother’s role, too.

“When I was young, it was seen as a scandal that I was being allowed to play. My father, uncle, and the people in our village wanted me to be married early. It was my mother, an uneducated woman who had never left the village, who stood up for me. She never played hockey herself, but if it wasn’t for her, neither Kanika nor I would have been hockey players,” she says.

Having come this far, Pritam is clear she doesn’t want the Siwach hockey line to end with Kanika. “I’ve already told my son that I expect him to get married in three years. I want a grandchild I can start teaching hockey to! By then, I hope I’ll have less work at my academy and can focus all my attention on that child!” she laughs.

Published on Nov 24, 2025